“War was a hell of a thing”. So says Henry Spencer, who as a young man from Blenheim was eager to sign up when war was declared in September 1939. After enlisting with the army, Harry would see action in Greece, Crete, North Africa, the Middle East, and Italy before returning home at the start of 1944.

His story is one of six complied by Jo Bailey, each one relating the experiences of individuals and their families throughout WWII. Using interviews, wartime diaries and written memoirs, this book contains the recollections of people from a diverse range of backgrounds within a carefully constructed framework that is supported by thoroughly researched historical detail.

Eva was only a child living on a farm near the outskirts of Rotterdam when it was commandeered by the Germans. Little did she know that her trips to a barber in the city provided hidden notes that where aiding the Resistance. Naylor, a navigator from Christchurch, also assisted the Resistance, although decades passed before it was revealed that he flew ‘moonlight’ missions to deliver supplies and support agents. Bram’s recollections are of a childhood in the Dutch East Indies being torn apart by the Japanese invasion, and of his father’s incarceration in a POW camp, whilst Ronnie’s upbringing in the UK resulted in him being sent to Australia as part of the Child Migrant Scheme. Members of the Wegrzyn family together recall the atrocities of being sent to a forced labour camp in Siberia.

However, despite having lived through such different aspects of a devasting conflict, this compilation reveals that these people have a lot in common. All suffered from the brutality of war, and many witnessed its horrors. Most recount their sheer struggle for survival and reveal a level of endurance that can be almost impossible to comprehend.

They speak of courage and compassion. Of bravery and heartbreak. Of hope and great gratitude. And all of them are, or eventually became, Kiwi’s.

History may recall the dates and places, the long lists of facts and figures, that help future generations to understand what once occurred. But it is the effort of writers and researchers such as Jo Bailey, and stories such as these, that bring us truths about humanity during wartime in a way that is both deeply personal and incredibly poignant. And although we may reflect during commemorative services for Anzac Day, Passchendaele or the Battle of Britain, it’s also works like ‘Never Forget’ that ensure the individuals who lived through such events will be remembered.

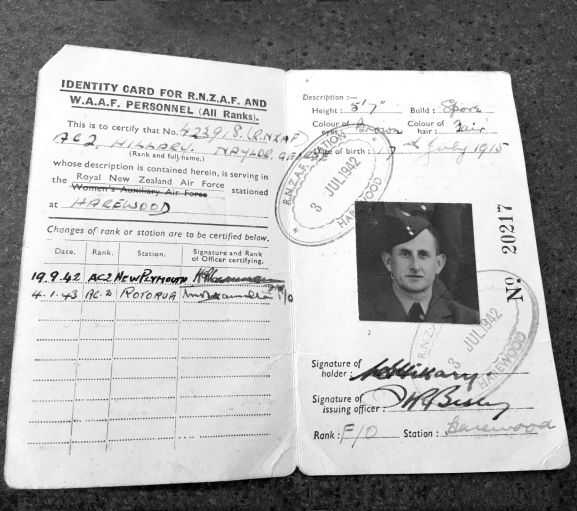

This extract from Jo Bailey’s book ‘Never Forget’ features part of Christchurch man, Naylor Hillary’s story. Naylor served with the RNZAF, and later with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s top-secret Special Operations Executive 138 Squadron, which flew agents and supplies behind enemy lines. The interview with Naylor was carried out when he was 101 years old.

Tempsford Airfield became associated with some of the war’s most highly decorated agents such as Peter Churchill, Violette Szabo, Nancy Wake (known as the ‘White Mouse’ who was born in New Zealand, grew up in Australia and by 1943 was the Gestapo’s most wanted person), Andrée Borrel, Lise de Baissac, and Wing Commander Yeo-Thomas (known as ‘The White Rabbit’).

They were among almost 1000 brave agents and operators spirited out of Tempsford by the courageous flight crews during operations.

In July 1944, just before Naylor’s crew arrived at Tempsford, the 138 Squadron converted from Halifax aircraft to a specially adapted Stirling Mark IV, a modified version of the Stirling Mark III bomber they had trained in at Wratton Common.

The nose gun was removed to provide better vision for the bomb aimer, who in 138 Squadron, acted as the second navigator. He was seated in the nose of the aircraft and with a clear view of the terrain, it was part of his job to call out the landmarks to Naylor as they approached.

The mid upper gun turret was also removed, with the gunner becoming a dispatcher instead. His job was to push supplies and agents out of the ‘Joe Hole’ or large trap door in the floor. The cargo might contain anything from arms, ammunition, wireless equipment and food, to clothing, medical supplies, and even pigeons.

“Whatever the agents needed, we tried to fly over to them,” said Naylor.

Some of the items were packed into large cylinders capable of holding around 220 pounds of weight each, which were carried in the Stirling’s bomb bays. Other heavier equipment, such as bicycles and bicycle tyres for the French, and skis and sleighs for the Norwegians, were attached to parachutes and carried inside the aircraft ready to be pushed out by the dispatcher. Naylor said the Stirling Mark IV was well equipped for navigation work.

“The chair was a high back office chair and there was plenty of room on the table for working. Rather unlike a Lancaster where I had to sit on a bare stool.”

Training in low level flying continued for Naylor’s crew when they first arrived at Tempsford. The area was very flat and they practised hedge hopping, or coming down to tree level and just rising up over the top.

“I’m afraid we must have scared the life out of a lot of farmers and animals, who would have been shocked to see a four-engine bomber flying at such a low height. But the training was needed for the pilots.”

Naylor’s crew didn’t have the most auspicious start with 138 Squadron, when flying their first three missions between 9–14 August 1944. They flew in Halifax and Oxford aircraft rather then their usual Stirling, and had three different skippers, instead of Flight Sergeant Banbury. While carrying out their first war operation into France, where they dropped five containers, nine packages and 20 pigeons, the aircraft was damaged after clipping a tree during low level flying.

“We came back to Tempsford with a tree branch stuck in the wing, so a new wing had to be put onto the aircraft. We weren’t very popular. On the next trip, which was a local exercise, we came back with a very large seabird in the wing, which had to be changed again. It wasn’t the best start.”

By 15 August 1944, Doug Banbury was skipper again, and by the time they completed their first war operation as a crew to France on 28 August, Naylor was learning just how critical his training on dead reckoning would prove.

“The big bombers flew much higher than us, and had additional radar assistance, but once we left the English radar system, we were on our own, a lone plane in the night sky relying entirely on observing where we were. A lot depended on the navigator being able to pinpoint landmarks, and fix our position at any one time, so that alterations in the wind could be adjusted immediately. The wind was a major factor when plotting the course, as you had to correct for it to get a direct line to the target.”

Any agents being spirited out of Tempsford, were kitted out in the barn at Gibraltar Farm before the flights, with parachutes and other equipment such as suitcase radios. Final checks would be made to ensure none of their clothing had British labels or they were carrying anything else to betray their identities. The agents were often issued with suicide pills to save themselves from torture should they be captured. Naylor says the crew had little contact with the many agents they dropped behind enemy lines.

“We weren’t allowed anywhere near the barn, and the only crew member who got to meet them personally was our dispatcher, who had been specially trained to look after them.”

The target for each operation was a pre-determined location, generally a clearing in the wood or an open field, where the aircraft would drop agents from about 700 feet, and supplies from around 450 feet. With no fighter escort for their missions, Naylor’s crew often had to contend with flak and fighter defences.

“We quickly discovered that once we were through the defences we could rise to a reasonable height to make it easier to map read across the countryside and get to the right height to make the drop.”

Landmarks such as rivers, roads and railways were critical to the navigation. The only help from the ground was torchlight, with the brave men and women of the Resistance flashing a pre-arranged letter signal in Morse Code, and arranging themselves into a pattern to indicate the dropping or landing zone.

“As we came to the zone, the bomb bay doors were opened and the canisters released by parachute. Other goods inside the aircraft were tossed out attached to parachutes, to hopefully land as close as possible to the reception committee.”

Sometimes the planes were prevented from reaching the target due to bad weather or enemy fire. Wind yet again, was another challenge, as if packages were blown too far from the drop zone and found by the Germans, an entire local district could be put at risk of the Gestapo’s scrutiny.

“Not every drop was successful. If we got to a site and the torch signal was wrong or we had any doubts about the people on the ground, we just turned around and went back with our load.”

Once an operation was completed at the drop zone, Naylor would plot the course for their return, avoiding known fighter stations and areas where there was a lot of defensive flak. The concentration required to complete these sorties was immense.

The work carried out by 138 Squadron was so secret that even Naylor’s crew didn’t discuss the actual locations of the operations amongst themselves. This was a much different set up from a normal bomber squadron, where its 25 or so crews would get together for a joint briefing before a big bombing raid. At Tempsford, each crew was briefed individually about their missions, and didn’t share the information with other crews in the squadron.

“Although we were all airmen living on the base together it was a difficult situation as crews were taking off at different times, and doing such secret work we couldn’t discuss where we’d been or why. The 138 Squadron had separate quarters from the crews in the 161 Squadron. They did more of the quick pickup work, landing behind enemy lines in smaller Lysander aircraft to collect people who needed to escape or to return to England with vital information.”

Naylor said his crew was very close, and slept in the same huts, apart from the officers.

“They would come over to our huts to socialise but we couldn’t go to theirs.”

From the personal collection of the late Naylor Hillary.

* * *

A typical day at Tempsford depended on whether or not Naylor’s crew was on ‘ops’. The day started when the list of crews required for the coming night was posted on a board outside the office. If Naylor’s crew were flying they would attend a brief, which took place a few hours before takeoff.

“The pilots were included in a second brief with the navigators when the actual targets were disclosed and the general conditions for the night were discussed, with the type of weather likely to be met and amount of cloud and so on. Then the navigators were briefed individually about a suggested route to the target, including the possibility of meeting enemy opposition on the way and how to avoid that.”

Navigators, like Naylor, were the hardest working members of each crew. After the briefing they were issued with a map of the area where they were flying, and a vague chart to enable them to plot their course.

“It was necessary to work out each individual leg of the course, as well as the compass readings for the pilot, both to the target and for the way back.”

Once the brief was concluded there was a short time available to relax before takeoff. From there, the navigator would take over the directions the plane was to fly.

If there were no operations on a particular day, the crew’s time was more or less its own. Naylor enjoyed visiting churches in nearby villages where he met a number of local families. For many years after the war he exchanged Christmas cards with a couple he met in Tempsford, and later in his life continued to correspond with their daughter, who still lived in the village.

He said the crew had a ‘very happy’ time at Tempsford and the nearby village of Everton, which had a pub that was popular with some of the airmen. The journey back to base included a downhill cycle, with a sharp bend at the bottom, where several of Naylor’s colleagues came adrift as they returned late at night after a few drinks. The Station Commander threatened to put any airman on defaulters who reported in sick due to not taking the bend.

With their flight schedule dictated by the moon, Naylor’s crew had a fortnight’s leave each month, which was different to a normal bomber squadron. They were required to spend one week on station, but were free to travel during the second week.

“We were fortunate. I had a bike and was given free rail passes to go anywhere in the United Kingdom. I was keen to see as much of England, Wales and Scotland as I could.”

Each leave Naylor would visit new areas. He met some hospitable people through an organisation in England that arranged for local families throughout the country to host service people when they were on leave.

Naylor’s friendship with Ida Penny continued to grow, and he visited her in Millom when he could. Towards the end of the war he bought a ‘baby’ Austin car at the airbase, which he would drive to see her.

“If a British airman was killed or failed to return, all his effects were sent home to his family. However if the airman was from the Commonwealth, his belongings were auctioned off with the proceeds sent home. I bought the Austin car for £8, which had belonged to someone from the Commonwealth who didn’t come back.”

Naylor’s crew flew seven war operations to France and Belgium in August and September 1944. In October they started flying into Scandinavia, including two operations to Denmark where low flying was easier due to its flat terrain.

The following month they flew to Norway for the first time, where the operations would prove some of their most challenging and exhausting of the war. Return flights took an average of seven to nine hours, requiring the intense concentration of all of the crew, particularly Naylor. They often wouldn’t return from those operations until three or four o’clock in the morning.

“We had to leave late in the afternoon and fly over the North Sea before dark. Pinpoint navigation was required to find the dropping zones, which were usually in a valley or somewhere like that.”

During one of these missions Naylor’s precise observational and navigational skills avoided certain catastrophe for his crew. They were flying behind another plane from the squadron to drop people into Norway, when there was a sudden wind change. Naylor managed to access the last of the English radar and believed the planes were going off course. As the planes reached landfall in Norway, Naylor’s unease continued to grow. The skipper, Doug Banbury had been told to follow the other plane, which was being directed by its own navigator. Naylor told Doug he thought they were in the wrong place, and given the great trust he had in Naylor’s skills and instincts, the skipper heeded his advice to fly further along the coast until their exact location could be determined.

Within seconds of realigning the aircraft, the plane they had been following was shot down by enemy fire after flying directly over an enemy fighter station. Naylor’s crew watched the tragedy unfold, realising just how close they had come to meeting the same fate.