Eighty years ago, during World War Two, one of the most daring and ambitious military operations in history took place in Holland. In order to shorten the war, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (known as ‘Monty’) proposed a plan to use airborne forces to capture vital bridges across Dutch rivers, including the Rhine. This would allow the stalled Allied advance to penetrate into northern Germany and even race towards Berlin itself.

Codenamed Operation Market-Garden, three key bridges were targeted and consisted of airborne – ‘Market’ – and ground -‘Garden’ – forces. The American 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions would seize those at Eindhoven and Nijmegen respectively, while the British 1st Airborne Division and 1st Polish Brigade would capture the big prize – the bridge at Arnhem over the Rhine itself, the last natural barrier into Germany. British XXX Corps would punch a narrow thrust to each town along a single road, securing each bridge and then on into Germany. To carry three divisions by air in aircraft and gliders could not be done with the available aircraft, so reinforcements and supplies would have to be dropped on successive days following the initial drop. Resistance on the ground was predicted to be light, and the operation was to be carried out in daylight, unlike on D-Day, a couple of months before.

Into action and disaster

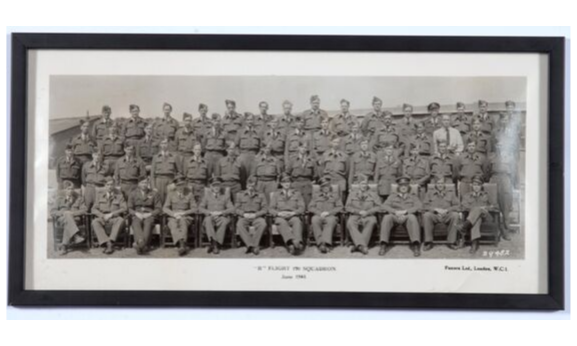

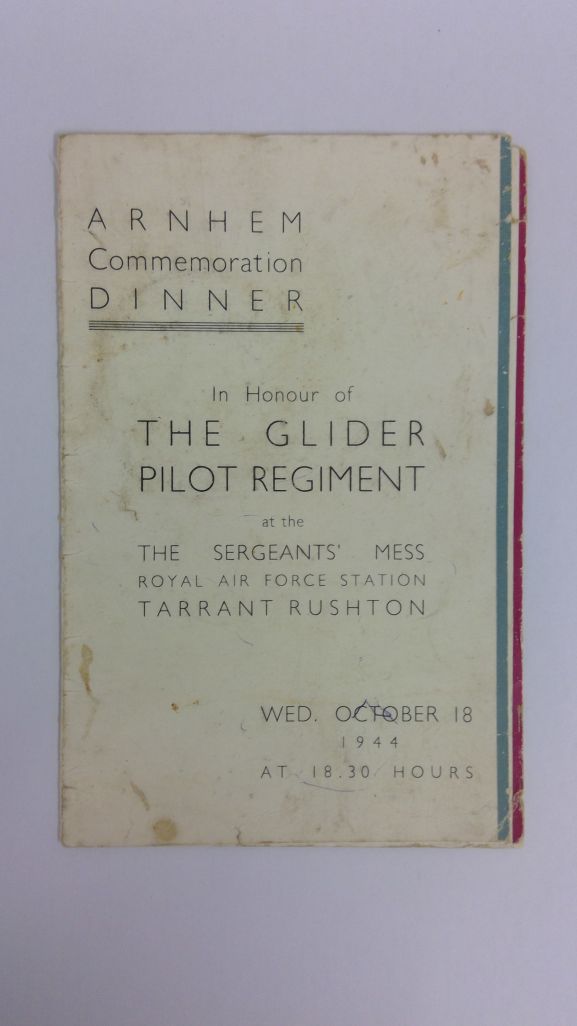

The RAF transport and glider towing squadrons of No. 38 and 46 Groups, like the bomber, fighter and coastal squadrons, contained many RNZAF personnel among the crews. On 17 September a huge aerial armada of transports carrying paratroopers and towed gliders carrying guns, vehicles and air-landing troops crossed the Dutch coast and began to land on their drop zones. Very few losses were suffered in aircraft on the first lift.

The Americans captured their two bridges at great cost. At Arnhem, things began to go very badly after a promising start. Despite securing one end of the bridge at Arnhem, the lightly armed British forces found they had dropped onto some resting armoured units of the elite Waffen SS. Over the next few days, fierce fighting took place and the British were squeezed into a smaller and smaller pocket on the north side of the river. Drop zones were lost, with reinforcements (including the Poles) and supplies being dropped onto German troops also lost. Eventually, the survivors were evacuated across the river, but with Arnhem bridge still in German hands, the operation was a failure. Nearly 3,000 British and Polish troops were killed or wounded and a further 6,000 became prisoners. The RAF also suffered heavy losses – 370 air crew, including five New Zealanders.

Tasked with supplying the airborne troops, the airmen of Transport Command faced enormous danger. In all, five Victoria Crosses were awarded for the Arnhem battle – four for the British Army and a fifth for British RAF Dakota pilot Flight Lieutenant David Lord, who continued on his supply drop on 19 September despite being on fire, before crashing to the ground in flames. Lord’s sacrifice is perhaps symbolic of the extraordinary bravery in the face of such danger of all the Transport Command crews flying in support of this ill-fated defeat. There were many stories of bravery and sacrifice among the New Zealand air crew too. This is the story of the fates of three New Zealanders who took part.

‘Superb handling of his aircraft’

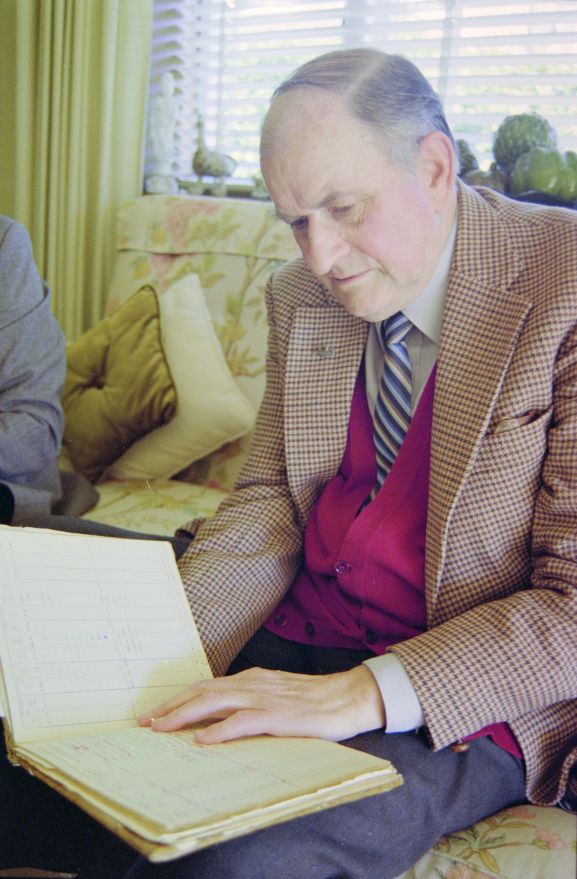

Flying Officer Larry Siegert of Fairlie would later become the Chief of Air Staff, the highest-ranked member of the RNZAF. In September 1944, he was a young pilot with No. 190 Squadron RAF, flying Stirling aircraft on Special Duties, which included airborne operations.

In an interview in 2005, he recalled his experiences on those fateful days in 1944, which remained vivid over 60 years later. Among the first aircraft to drop troops over Arnhem on 17 September to mark drop zones and landing zones for paratroopers and gliders, Siegert vividly recalled:

“I always remember when we dropped the paratroops, it was a beautiful day like this. The fields were there at Oosterbeek and we went in and dropped our paratroops and as you turned away you could see them – just like mushrooms on the ground. Beautiful.”

Emerging unscathed, the huge undertaking would require more trips by surviving aircraft like Siegert’s. On subsequent days, German ground fire increased and fighters started to make their presence felt:

“The next day we took supplies into Arnhem. Things were getting pretty hot – the Germans were surrounding the place.”

By 21 September, the situation was desperate on the ground and in the air:

“The third day we went over and I had a problem as we got near the dropping zone at Arnhem – a swarm of aeroplanes came out to meet us and I thought they were our fighters, but they were German Focke-Wulfs!

They got stuck into our aeroplanes, shot our Wing Commander down and Squadron Leader… they went down in flames in front of me and then I dived in and dropped our supplies on the besieged chaps at Arnhem and then we headed for home. We were attacked by Focke-Wulfs all the way to the Dutch coast. We think we shot one down. It was awful. You had to do steep turns away from them as they came at you and you could hear their cannon thudding into the aeroplane behind you. Several of the people on board – the army despatchers and my wireless operator were badly shot”.

Only two aircraft of No. 190 Squadron returned home from the mission. Larry Siegert was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions.

‘The bravest thing they ever saw…..’

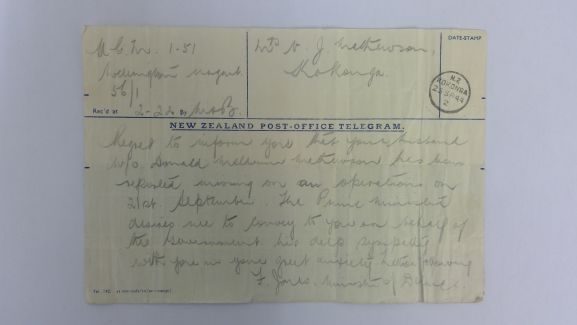

Among the crew of RAF Wing Commander Graeme Harrison’s Stirling which Siegert saw go down in flames was 36-year-old navigator Warrant Officer Donald Mathewson. He had joined the RNZAF from his home in Kokonga, Central Otago and trained in Canada. Along with him in aircraft LJ-982 was fellow New Zealander Warrant Officer Barry Brierley of Wellington.

The crew had towed the glider of the British 1st Airborne Division commander, Major General Roy Urquhart on the first day of the operation and were leading the squadron formation on 21 September. Having dropped the supplies, they were turning away to climb out when the German fighters struck. Two crew bailed out and died as they were too low for parachutes to open and the rest, including two army despatchers died in the crash near Zetten. Buried nearby, they were later moved to Oosterbeek Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery.

Mrs E. Mary Harrison, the wife of the British pilot, later wrote to Don Mathewson’s widow, Violet, In New Zealand describing an anniversary pilgrimage she made to Arnhem after the war to see the graves. She wrote:

“I actually met two airborne men who were taken prisoners at the bridge and watched our Stirling come in, leading. They said it was the bravest thing they ever saw in the war”.

‘It was a very difficult thing’ – Larry Siegert

With so many losses, No. 190 Squadron was virtually destroyed for now. The survivors tried to process what had happened at Arnhem. On being asked 60 years later if the experience shook him, Larry Siegert could only reply:

“I’ll say. I sank a few beers that night… It was awful. But you just went back to your Nissen hut and sleep it off. But there was no one else in the Nissen hut – it usually had about eight beds, four on each side, but I was the only one left. All the others had been shot down… anyway, that was Arnhem, a horrible experience”.

Like so many Allied soldiers and airmen, Mathewson and Brierley are buried at Oosterbeek Cemetery, where the local Dutch school children remember and are still given the responsibility of looking after a particular grave and to place flowers on them on the anniversary of the bold attempt to liberate Arnhem, take the bridge and hasten the end of a terrible war.