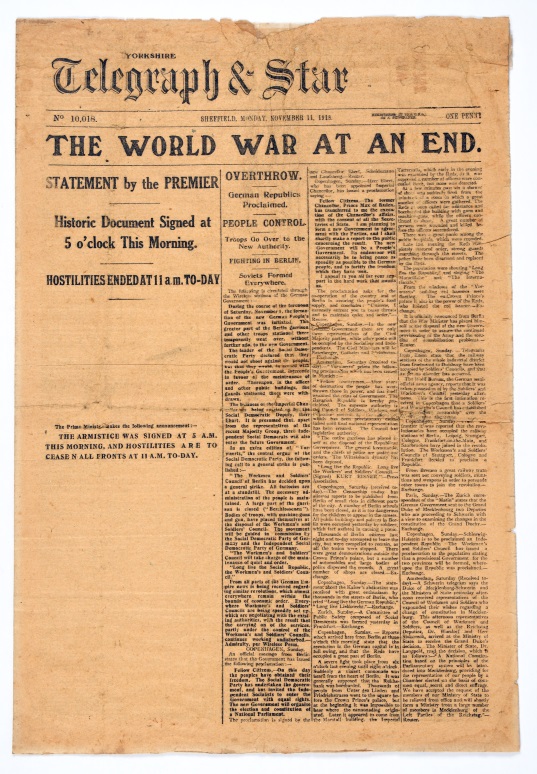

At the 11th hour of 11 November 1918, the guns on the battlefields of Western Europe fell silent, marking the end of what would later be known as the First World War. Newspapers around the world reported the momentous news in detail, and people across the world rejoiced.

New Zealand airmen serving overseas reacted to the news in a variety of interesting, and sometimes surprising, ways. Some recorded their reactions in diaries, letters and subsequent memoirs and interviews, some of which are now in our archives.

The Western Front

Malcolm ‘Mac’ McGregor had been in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) for two years and was an officer, with all the privileges that entailed. An anecdotal story is told in his biography “Mac’s Memoirs” that on 10 November 1918, he and fellow New Zealander Keith Caldwell were enjoying a pre-dinner drink in the officers’ mess of No. 85 Squadron RAF when a mechanic broke with military custom and rushed in to deliver the joyful news of the Armistice being signed the following day.

This man, not being an officer, was not usually allowed into the mess. Perhaps because of this breach of protocol, McGregor pretended to throw his glass at the unfortunate man, bellowing:

‘Out of this, you blighter and take your dismal news with you’!

This is perhaps also an indicator that flying and war had become a ritual and the prospects of it now ending was difficult to process for men like Mac McGregor.

United Kingdom

Meanwhile, in the UK, on hearing of the imminent Armistice, Eric Croll flew south to London from his training station:

‘The drill was to find a railway line and read the name of the first station – Cheam – never heard of it but a little further on an aerodrome so landed at CROYDON. Met all the boys in the mess and celebrated the late war then across country through the still pouring rain across south-west London and keep well clear of those blinking balloons at Roehampton. Back at Northolt things were really hotting up but a feed and off, to London and straight to our rendezvous the Savoy Hotel. Down to Trafalgar Square where the crowd were really celebrating and those rough Australians had lit a bonfire of bus-destination signs and the wooden wheels of German guns — This-was against the plinth of Nelson’s Column…… Should have been content with flirting with death as they say for two years.’ The war did not end for us – certainly we were not dogged everywhere by a trail of black puffs, Hun A.A. [anti-aircraft] fire but we were a bit reckless now I fear and were encouraged to go on flying for some reason. They never trusted the Hun and it was only an Armistice’.

Some were just bewildered by the fact that it was all over, after four years of training, fighting, concentration on one goal and exposure to all the associated propaganda and nationalism. Second Lieutenant John Lochhead, a Cantabrian and graduate of the Canterbury (NZ) Aviation Company (CAC) at Sockburn, was just finishing his long period of training near Portsmouth when the mundane cycle was broken. He wrote briefly in his diary:

‘Fine day. Went to lectures in the morning, then on general parade where it was announced that the Armistice had been signed. Nearly everyone in the camp was stunned’.

Ironically, Lochhead’s diary records that he had visited Lord Nelson’s famous Napoleonic War flagship HMS Victory the previous day – perhaps he should have guessed what might be about to happen!

Egypt

Other New Zealanders were training in more exotic locations. Fellow CAC graduates Edwin Wilding and Ross Brodie had been sent to Egypt from Britain earlier in 1918 to complete their training. They were at the Aerial Fighting School in Heliopolis when the Armistice was reported as imminent:

Wilding followed the progress of peace in the newspapers and wrote briefly in his diary on 10 November:

‘The war seems to be just about over. Awaiting Germany’s reply’.

Then, on the 11 November he wrote:

‘Armistice signed. Terms wonderfully good for us. Germany is quite finished alright. People quite bright.’

The following day he wrote,

‘Great processions etc in Cairo – quite a lot of damage done by Tommies [British soldiers].’

Ross Brodie recorded that this unruly behaviour also occurred at the local army camps:

‘Word came through after dinner that the Armistice had been signed and what an awful cheering was going on over Polygon Camp way and about 10.30 a big blaze was seen over Polygon Camp – it looked as if several huts had caught fire.’

For Brodie, the war was not over – he flew in support of operations to quell the Arab uprising which occurred after the end of the war, not returning home until later in 1919.

Off to Russia

Early in 1919, Gordon Pettigrew would find himself on the way to serve with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in Russia fighting the communist revolutionary Bolsheviks. According to correspondence in the 1970s, he reckoned he got this unpopular assignment,

‘Because to celebrate Armistice Day, he took up a New Zealand soldier and they buzzed Brighton Beach, looking especially for senior officers and brass hats, who were beaten up and bombed with two large bags of oranges and apples they had bought. He was given a tongue-lashing the following day and selected for Russian duty shortly afterwards.’

Ironically, he started a fruit farm in Motueka on his return to New Zealand!

The Final Losses

The Armistice was also a time of great sadness. Many families had lost relatives in the fighting and New Zealand was in the grip of the influenza epidemic.

In the face of this, two individual family tragedies might seem quite insignificant but they are still poignant 100 years later.

On 11 November 1918, Second Lieutenant Allan Macdonald took off in an Avro 504 with a flight cadet he was instructing from Scampton in Lincolnshire. During the flight, the aircraft stalled and crashed into the ground. The cadet survived, but Macdonald died. He was buried in Stamford nearby. His family posted these words in the local newspaper in early 1919, an indication of the cruel blow they had suffered:

‘So Dearly Loved, So Sadly Missed’

But Macdonald was not the last to die. On 9 November, Duncan Sloss, another Canterbury Aviation Company graduate was flying a bomber over a German target when he was attacked by 12 fighters. Both he and his observer were wounded and made a forced landing. Admitted to hospital he lingered for over a week, but died on 23 November 1918, the last New Zealand airman to lose his life as a result of enemy action. His brother had died in the New Zealand Army on the Somme in 1916, making it a double tragedy for the family.

Epilogue

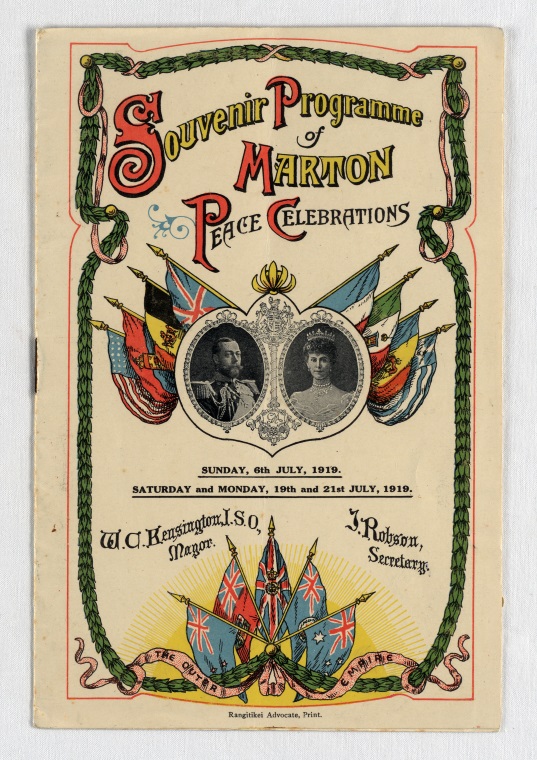

As Eric Croll reminded us earlier, the war did not actually end on 11 November. It would only be in the following year after lengthy negotiations and the imposition of harsh terms on Germany that the Treaty of Versailles would be signed and New Zealand could finally move on from the First World War and truly commemorate the end. But in a way, this was not really the end. Within 20 years, the next generation of New Zealand airmen would once again witness a devastating war and travel to serve overseas. But that, as they say, is ‘another story’.