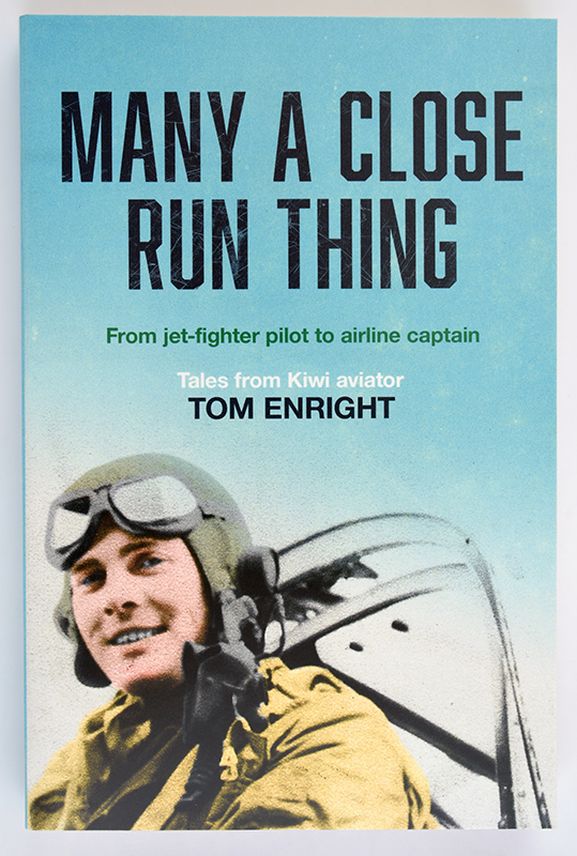

New to our Museum Shop is the published memoirs of Tom Enright, a veteran New Zealand pilot from Central Otago. Tom joined the RNZAF in 1951, and on graduation, was recommended for a cadetship with the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell, England. His first 20 years flying was in a variety of military aircraft, including Vampires and Sunderlands, and he was a member of the famed RNZAF Vampire aerobatic team. He then spent the next 25 years as an airline pilot. This is an extract from his new book Many A Close Run Thing (Harper Collins NZ), which is now available for purchase from the Air Force Museum Shop:

Wild ride

One day, completing a training flight in an FB5 at Ohakea, I was downwind runway 15, number two for landing. Fuel at 15 minutes remaining was low but not concerning. Number one ahead of me in the circuit was a Devon, a rather slow piston-engine aircraft, so I extended the downwind leg of my circuit to allow time for the Devon to land and clear the runway. When I turned onto finals, however, the Devon was still on the runway. I was now starting to watch my fuel level closely and decided that if I had to go around, I’d need to ask for landing priority due to low fuel state. Sure enough, came the call from Ohakea Tower: ‘Vampire on finals, go around. Runway obstructed.’ I advanced the throttle fully forward, and the Goblin engine came screaming up to full power. I banked to the left to start a tight circuit.

Boom!

The explosion from my engine brought the whole station to its feet. Klaxons blared and emergency crews raced for their vehicles as the crash alarm echoed round the station. Quickly, I had to decide what to do. My brain racing, I considered my options. Bail out? Far too low with no ejection seat. Turn back to land on the airfield? No, much too low. The only choice was a forced landing straight ahead. I made a hurried distress call: ‘Mayday. Mayday. Mayday. Engine failure. Forced landing ahead.’ Frantically, I searched the farmland ahead for the best landing path.

A recall of a lesson learned flashed through my mind: a Vampire’s forced landing in which the aircraft went through several fences but did not sustain serious damage. I could select the best landing ground ignoring fences. No way was I going to stop in any field at the touch-down speed of a jet fighter. The best-looking ground lay to the south-east. Discounting the several fences on it, I selected a path. There were also two ditches to cross: unwelcome, but they looked survivable. A third ditch in the distance was too far away to be scrutinised. The direction selected was into wind.

Setting up an approach at 120 knots, I considered another lesson recently learned: according to a USAF publication, an all-wheels-down landing was the safest configuration for a tricycle-type undercarriage jet fighter in a forced landing. I therefore selected gear down (a decision which probably saved my life) and began furiously pumping the emergency hydraulic hand pump, knowing the failed engine wouldn’t provide sufficient pressure to lower the gear. Next, jettison the cockpit hood – I snatched the black and yellow handle and the Perspex canopy sailed off over the tail. With the ground fast approaching, I steeled myself to fight every inch of the way in the wild ride ahead.

At 100 feet bleeding off speed, I chose my touch-down point. Flaps were selected but probably weren’t extending due to low hydraulic pressure. Clearly I was going to impact three fences just ahead with two more in the background. Crash! Bang! Clang! I flew through the first three fences and bounced through the first ditch, taking out hundreds of metres of fenceline. Wreckage was flying everywhere. On the ground and riding rough, I bounced through another ditch – crash! Going through the fourth fence I hit a totara post, a tough pole which fractured the mainspar of the starboard wing. The post broke into three pieces and one piece clipped my helmet as it hurtled by. Phew, close-run thing there.

Then I was through the fifth fence and skating on slippery newly mown hay, still doing about 80 knots, braking with all my might in the belief my main gear wheels were down (they weren’t). But now I saw I was in deep trouble as the third ditch loomed up. Not apparent from where I made the forced landing decision, the ditch was deep with a solid, vertical far side. I couldn’t see how I could possibly survive the coming impact and resigned myself – it was curtains for me! Well, I’d fought as hard as I could but because I was still moving at about 70 knots speed approaching this steep bank I could do no more. The closer the ditch came, the more the adrenaline pumped and the slower everything seemed to move.

I expected to die. Interestingly, I wasn’t frightened. There was no flashback of past life, just an awareness that I was about to learn the mystery of the ages, what lies on the other side. Then came the heaviest imaginable impact as I struck the far ditch, and slowly, oh so slowly, slowly, a jet black curtain came down over my eyes. I lost consciousness. I guess that’s what it must be like to die.

My decision to lower the undercarriage now paid off. The nose gear, locked down, struck violently and sheared off. The main gear, not locked down, was dragging on the ground. The fuselage was held in a nose-high attitude. Had it been in a nose down configuration it would have speared into the ditch far bank with fatal results. The nose gear’s shearing off absorbed some of the kinetic energy of the crash.

Sitting on a parachute, I went through the bottom of the seat and the floor of the aircraft as well! This dissipated more energy as the airframe crumpled. Each of these factors absorbed energy, and amazingly I escaped a broken back. The aircraft had enough of a nose-high attitude to bounce out of the ditch, leaving a deep gouge.

I came to. Unbelievably, I was alive! I smelled smoke – a magnesium fire – and leaped out of the wrecked cockpit and ran! A local farmhand reckoned I did the first hundred yards away from the wreckage in 8.9 seconds. Marvelling at my luck, I watched the rescue vehicles crashing through the farmer’s gates and across his fields.

Close-run thing? You bet!

In the end, the episode cost me money! In the bar at my celebratory party I said that approaching touchdown, I took one wire out of the first fence, three wires out of the second, and five wires out of the third, and I reckoned that was a pretty smooth let-down. At that a roar went up from the crowd, the ‘Line Book’ (in which outrageous statements are recorded) was called for and I had to shout the bar.

I was thankful to have walked away from that lot without a back injury and have taken care of my back ever since. The Air Force paid me a nice compliment by classifying the forced landing as ‘commendable’ and, surprisingly, not holding a court of inquiry. It emerged that an impurity in the metal of a compression blade had caused a typical crystalline fracture line. Nine inches (23 centimetres) of the blade came away and jammed in the engine casing. There was a violent seizure, sufficient to fracture all four engine mountings front and rear, and the turbine was mashed by a mass of metal. A magnesium bearing caught fire – magnesium fires generate their own oxygen supply (good old de Havillands!).

Sometime later, I happened to be in the RAF Changi mess in Singapore when an old Cranwell friend walked in and saw me. He started back as if he’d seen a ghost – as indeed he thought he had. He’d attended a funeral service for me at Cranwell. A rumour about the crash had turned into a report of my death!

What a pity I wasn’t at Cranwell that day. It would have been a hoot to be waiting in the bar when the churchgoers returned, to assure them the rumours of my death had been greatly exaggerated and to buy them all a drink!