Wallis Finlay was a Hamiltonian who had a distinguished flying career as navigator in the Pathfinder Force during World War Two, completing 106 sorties over enemy territory during the air battle over Europe. His letters home, donated to the Air Force Museum of New Zealand’s collection, give an extraordinary insight into life in one of the most dangerous roles in the air force.

Wallis Finlay volunteered for service in the RNZAF early in World War Two. He listed his occupation as slaughterman at the Westfield Freezing Company in Auckland. On 19 September 1940, a day before his 23rd birthday, he began training as an Air Observer under training with the rank of Aircraftman grade 2 at RNZAF Station Levin.

Two months later, on 20 November he sailed from Auckland across the Pacific Ocean on the troop ship HMT Awatea, bound for Canada where he was attached to the RCAF and No. 4 Air Observer’s School in London, Ontario. This was a long train ride from Vancouver on the West coast where they landed, and is located between Lake Huron and Lake Erie.

Air Observer was a trade that dated back to World War One when two-seater aircraft had an observer to keep a lookout for enemy aircraft, plan the route to the target, spot artillery fire by ground forces and sometimes operate the machine guns.

Over the years the role slowly morphed into more navigation with the role of Air Gunner becoming a separate job.

By the end of World War Two, the trade had been re-named Navigator, but those who had already qualified as an observer were still able to wear their ‘O’ badge.

After a short course at No. 4 Air Observers School, he was posted to No. 4 Bombing and Gunnery School at Fingal Ontario, just south of London. This is where he learned about how to correctly target, aim, and release bombs.

He regularly wrote to his mother mostly describing his life outside of the air force. Partly this is because he wasn’t allowed to mention specifics, for security reasons, but, perhaps, partly because he didn’t think she would be interested in the dull regularity of service life.

In March 1941 he mentioned barrack life and the importance of receiving letters from home. “It’s share and share alike as far as food goes. One chap opens a cake sent from home and they all crowd around like rats around a piece of cheese.”

He went on to say: “In three more weeks I shall have my left wing upon my chest. I shall be a fully blown Sergeant Observer and I’ve a sneaking feeling that we chaps will not see England but be sent to an out of the way place to do some patrol work.”

In early April 1941, before Japan had entered the war, he was posted to No. 1 Air Navigation School, in Rivers Manitoba, about 200 kilometres west of Winnipeg. This short course was advanced navigation training.

Image: 1984/019.2b

He wrote to his mother: “Generally lectures start at 8 but on this station they commence at 9 o’clock. This gives us ample time to amble through our morning toilet etc. The boys are now a domesticated mob. This morning our barracks look homy and comfortable. They are spit polishing, writing and reading. I feel that there is some peace left.”

After only a month he’d graduated and was heading for England from Nova Scotia in Canada’s East. In May 1941 he sounded a little dis-gruntled when he wrote “…even though I did top my class in the final exam, tis evident they don’t want brains. They want the talkative guy with legs on his belly. Enough said.”

After arriving in England he had a couple of months spare time before his first posting to No. 20 Operational Training Unit at RAF Station Lossiemouth in the North of Scotland. As the name suggests, this two month course prepared him for operations against the enemy by requiring day and night navigational exercises and also bombing exercises. At the start they flew in Anson aircraft before settling into crew groups and flying in Wellington bombers.

Image: ALB1307612055

In a letter to his mother in September 1941, just before finishing training and going on operations, he talks about walking and enjoying the English countryside in warm weather. Birds singing, the smell of harvested hay etc. He enjoys the mists because they stop the flying activities. He mentions the Bible that his brother Alan gave to him. “I’ll even admit that it is only on rare occasions that I pick up the Bible, but when I do I find encouragement therein.”

Wallis was posted to No. 57 Squadron at RAF Station Feltwell, flying Wellingtons. This is where the famous No. 75 Squadron were based and he would have met many other New Zealanders there, which perhaps would have made him feel more at home.

After his third operation and the day before his fourth, a 6.5 hour flight to Karlsrhue he wrote: “It’s a funny racket. For many days we do little, then away we’ll go. There’ll be preparation for a trip across the other side. There’ll be the trip itself. Then of course we do not see our bed for about 24 hours.”

In a letter to his family in November 1941 he describes what it felt to be caught up in a global war: “Now because a few can’t live in peace, I & millions of others must suffer all this discomfort.”

In the same letter he adds: “In England something always arises to mar the peace. No sooner had we lazily stretched our legs to the fire than the cursed air raid warning sounded. With surprising speed my host was up & gone. He went to his duties and I disgustedly ambled off to my bed.”

He talks a lot about the English fog – a nightmare for a navigator such as him: “On the evening of one of these days we’ll be sent on a trip to interior Germany. Taking off in this filthy weather is no joke but once the upper spaces are gained a new word is unfolded. Below, bank upon bank of white clouds stretch away towards all horizons. No earth will be visible. It is really amazing. The roar of the motors, the marvellous view on every side seems to be the opening of a new heaven.”

In January 1942 ‘B’ Flight of No. 57 Squadron moved to RAF Station Methwold where Wallis finished his tour of duty. Initially he flew with the pilot Sergeant Grey, but most of his 33 operations into enemy territory was done with the pilot Sergeant Williams. At the end of the tour he listed his crew in his log book.

The crew included: Sergeant D Williams (Pilot), Sergeant W Lovejoy (Second Pilot), Pilot Officer WG Finlay (Navigator), Sergeant W Pitches (Wireless Operator), Sergeant J Twynham (Front Gunner) and Flight Sergeant F Carter (Rear Gunner).

In an undated letter he describes an operation: “We came back from the other side one night. There was no moon. The clouds were very low. An hour or two after midnight we crossed the English coastline. It was a dim blur, and we could see the wild North Sea crashing upon the sands. Blacked out England gave away no clues. Swiftly the Wireless Operator pounded away at his set, the pilot guided our craft steadily onward. Two gunners and a second pilot carefully scanned the skies. True watch dogs of an aeroplane. Over my plotting table I wielded pencil and ruler. Closer & closer we drew near our drome, but it was dark and we failed to see the welcoming flarepath.”

“We found another and this one beckoned us in. Our pilot pushed our craft earthwards. He made a dandy landing. As soon as he had brought the plane to a stand still he turned on his radio and called up the control officer. A jabber of foreign lingo came back to us. Good heavens yipped someone, this isn’t England it’s France. We quivered, we shook, we cussed. Two of us commenced to destroy some of our most secretive stuff. Our second pilot, leapt from the plane and grabbed a man who came up to us. He snatched this gentleman’s cap and peered at the badge. Boldly displayed was our insignia ‘RAF’. He wasn’t a Jerry and our second pilot whooped out a yell of reassurance to us.”

“A few miles away from our drome there dwells a squadron of Czechs. That’s where we dropped down.”

In a letter to ‘Mother and all’ on 16 May 1942, he seems to wax lyrical about the beauty of nature in spring but doesn’t go too much into service life. “England in Winter is not the England of Spring, frankly one is grand and the other is vile. The sun will ever be my friend for without it I am gloomy, with it I am a man and contented.”

“During the grey months of winter the aeroplanes which flew about appeared to be speeding monsters of hate and venom and now they pass through the sunny heavens, they seem to be friendly inventions and part of the lovely world.”

After his tour of 33 operations, he was posted to a short course at the School of Air Navigation, from where he wrote: “I do not fly these days. My first dose of operations are over. I am having a rest. A funny rest. I have been posted up north where I am to take another short navigation course. It will take six weeks. Where I go then I do not know.” With a glint of positivity he wrote: “I think we are, at last, crawling up the ladder to victory. ‘Tis about time too.”

Then he went to No. 19 Operational Training Unit as an Instructor for a ‘rest tour’ at RAF Station Kinloss in Northern Scotland, where he stayed until February 1943 before moving to No. 10 Operation Training Unit at RAF Station Abingdon, west of London.

Near the end of this posting in March 1943 he wrote to his mother about his proud new accessory below his lip: “My moustache is a good one. Everyone says it suits me. One polite airman told me that if I didn’t have it my face would look like a fried egg.”

He also talks about good luck charms and how ‘Topsy’ came into his life: “The air force are a superstitious crowd. Nearly all have some little curio, a rabbit’s foot, a silk stocking, or a pair of natty panties or a lucky boot. There are dozens of little things which men carry & call charmed. I have an odd collection. Someone gave me a little silver boat, a Catholic gentleman gave me a little leather folder with a cross & a few words. I have a penny with the Lord’s Prayer on it. Stowed away somewhere I have a rabbit’s foot & a pink elephant. I have two lucky boots. And lastly, I have a few sprigs of Scottish heather. A dear woman gave me these. ‘Tis odd, but when a fellow makes friends they generally give him some little oddity saying that it is a charm to help keep misfortune away. Have I ever told you of Topsy? She is a pet. A Canadian girl gave her to me. She’s my pal. I have her always on my desk. Perhaps I’ve taken a fancy to her because she’s a black quaint red lipped doll. She came along on our honeymoon.”

By December 1942 he had married Sheila McGaw. In a letter to his mother in May 1943 he writes: “I do not like the instructional side of the Air Force life. ‘Tis too much like dull routine, but for Sheila’s sake I’d better stay put as long as I can.”

It’s clear that he had some concern about the work the RAF was doing when he wrote to his mother in April 1943: “I pity the German folk who are in their homes. Their hours of safety & peace are very few.” And he says about the raids: “I never like doing it. After all it is something that sounds like adventure to those that haven’t tried it. It is exciting but it isn’t fun.”

In September 1943 life as an instructor became too much, and he yearned for more action. He was posted to No. 109 Squadron at RAF Station Stradishall, northeast of London. This unit was part of the Pathfinder Force, flying the famous Mosquito aircraft from RAF Station Marham, North of London.

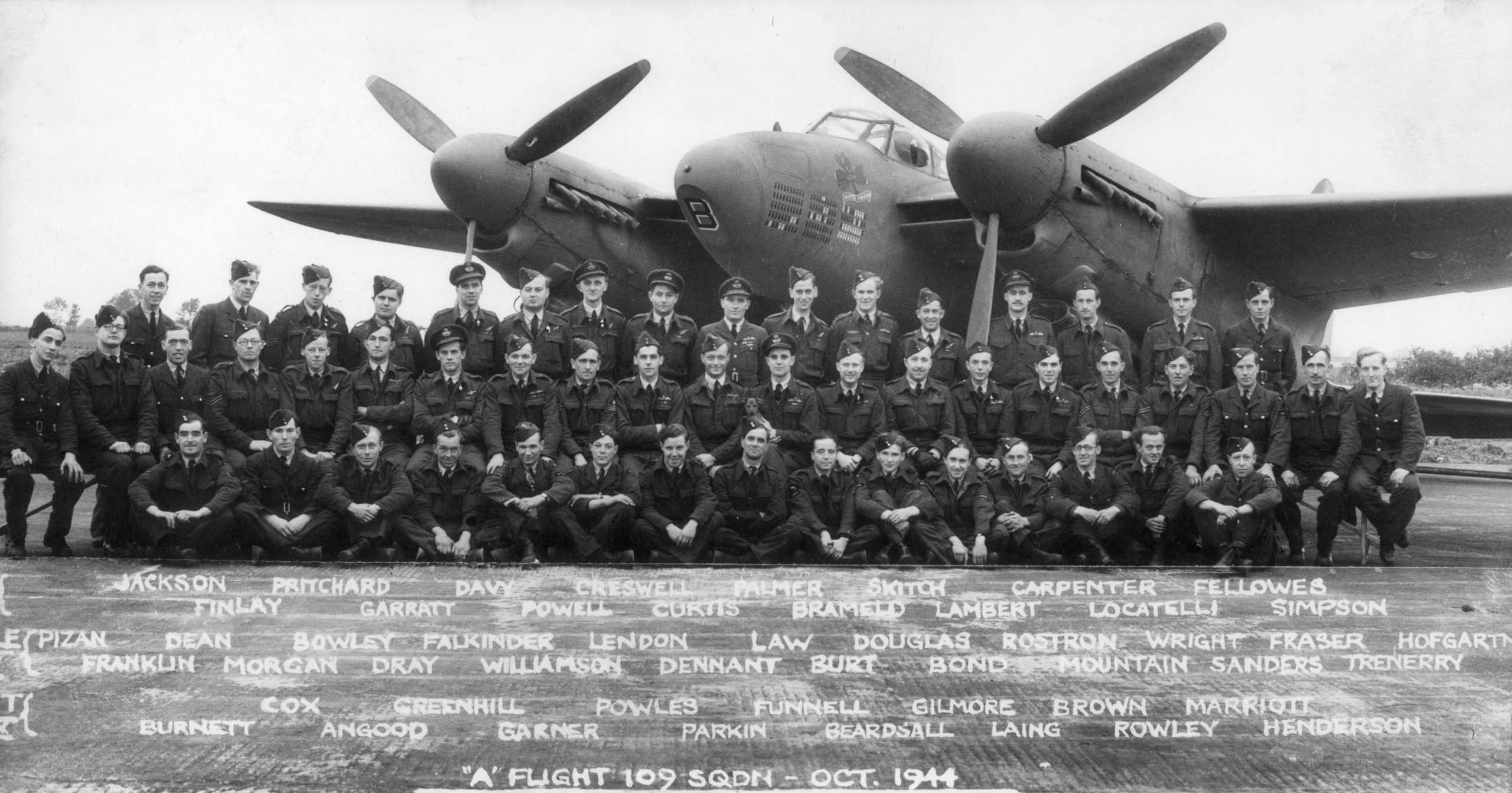

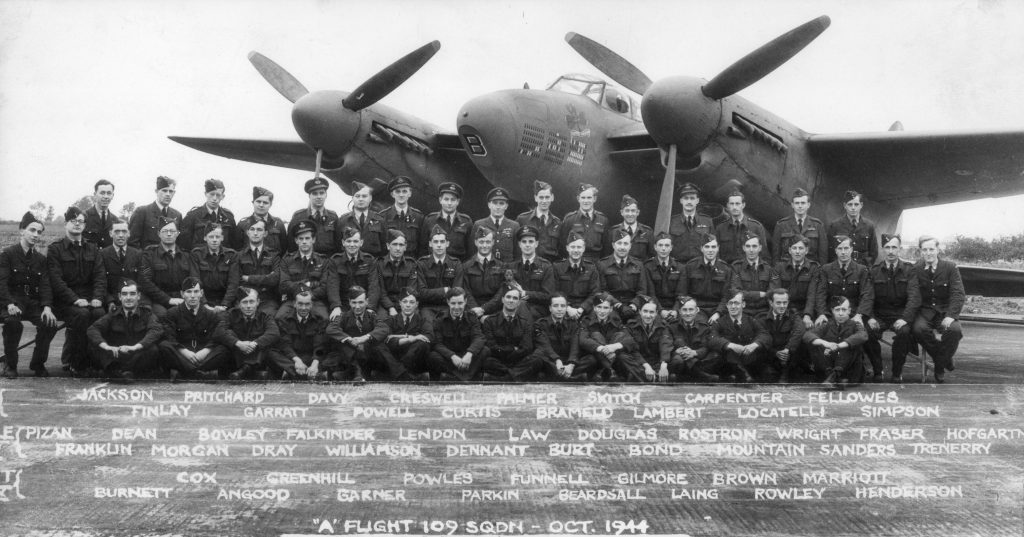

Group. ‘A’ Flight of No. 109 Squadron at RAF Station Little Staughton.

L-R: Back; Jackson, Finlay, Pritchard, Garratt, Davy, Powell, Creswell, Curtis, Palmer, Bramfeld, Skitch, Lambert, Carpenter, Locatelli, Fellowes, Simpson.

Middle; Pizan, Franklin, Dean, Morgan, Bowley, Dray, Falkinder, Williamson, Lendon, Dennant, Law, Burt, Douglas, Bond, Rostron, Mountain, Wright, Sanders, Fraser, Trenerry, Hofgartner.

Front; Burnett, Cox, Angood, Greenhill, Garner, Powles, Parkin, Funnell, Beardsall, Gilmore, Laing, Brown, Rowley, Marriott, Henderson. Image: 2013-076.59

The Pathfinders was an elite group whose job was to lead the main bomber force to the target, accurately drop marker flares so the rest of the bombers had something clear to drop their bombs on. The Pathfinders had special equipment in their aircraft which allowed them to accurately locate their target, even in heavy cloud cover.

In April 1944, while serving with No. 109 Squadron he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). In an undated letter to his wife he wrote: “I’m awfully drunk. But I love you such a lot. I have been celebrating my gong.”

Just six months later he was awarded a second DFC; a Bar to his first and in July 1945 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). In addition, the French Government awarded the Croix de Guerre.

The official citation for his DFC reads: “This officer has completed many successful operations against the enemy, in which he has displayed high skill, fortitude and devotion to duty.”

For the Bar to his DFC the citation reads: “This officer has an excellent operational record. He has completed many sorties, the majority of them against very strongly defended enemy targets, including Berlin. His high sense of duty and efficiency makes him a valuable officer to his Squadron.”

Only 62 members of the RNZAF in World War Two were awarded a Bar to their DFC.

The Citation for his DSO reads: “This officer has had a most distinguished operational career. He has been engaged on flying duties since early in the war and has participated in attacks on a great variety of targets, many of which were heavily defended industrial centres in Germany. Since the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross Squadron Leader Finlay has taken part in numerous sorties, and has fulfilled his tasks with outstanding efficiency and accuracy. Whatever the opposition he has invariably delivered his attack with precision and the utmost coolness. His work, both on the ground and in the air, has left nothing to be desired.”

Only 55 Members of the RNZAF were awarded the DSO in World War Two.

And the citation for the Croix de Guerre reads: “For exceptional services during in the liberation of France.”

For most of his 104 operations with No. 109 Squadron Wallis was teamed with the same pilot, another New Zealander, Flight Lieutenant Alan Dray. Dray was also awarded a DFC and the Croix de Guerre.

In By Such Deeds, by Colin Hanson, which lists all honours and awards to members of the RNZAF, Dray’s entry states that this crew “…also carried out pioneering Oboe (blind bombing) flights.”

In an undated letter to ‘the Twins’, written after the war had ended, and all restrictions around writing about such things were relaxed, he talks about his first operation to Bologne. “We got to the target quite easily, the docks showed clearly in the moonlight and we did our first run up. But I was keen and because we weren’t just right I wouldn’t let the bombs go. We tried again. This time the pilot forgot to open the bomb doors. Again we tried. This time I was so excited I forgot to press the bomb release tit hard enough. The fourth attempt was successful, it had to be for the men on then guns below were getting definitely hostile. I had the satisfaction of seeing our load burst clean across the docks. I thought the whole business just an exciting game.”

He wrote that a mission to Cologne on the night of 10 October, 1941, “…changed my whole outlook.”

“It was my first real lesson in warfare. Until that night I was as cocky as any farmyard sparrow. [Jerry] would pick on a certain aircraft, cone it in searchlights and then paste the daylights out of it with every gun he could bring to bear. Up until that time we had never been the sucker but on this night we were. All was dark, all was quiet. Just as we reached the outer fringes of the city a great blue searchlight flashed on and lit us up like a Xmas tree. He was the master light, a guide for all others & they immediately turned on us as we were bang in the middle of a flashing waving cone of searchlights. That, of course, was the moment for which the gunners waited. Shell after shell screamed up. The tracer came up as popping streams of reds, oranges, golds & greens.”

“The heavy shells burst in mushrooms of black-brown smoke. High in the sky the smell of powder is most unpleasant. We were all damp with cold perspiration and as frightened as doves. It takes almost five minutes to weave our way through & out of that mess. If you think 5 minutes a small moment of time please change your ideas because in an aircraft when you are the target it seems like eternity. The poor plane had many bruises. After that I was a subdued and wiser man with a much greater respect for the enemy.”

He describes a harrowing trip to Berlin on 7 Novmber 1941.

“We took to the air at 10 minutes to six, the hour when normal folk think of having their evening meal. The outward journey was quiet. Great layers of snowy white clouds obscured the land and sea. As a guess I would say it took about 3 ½ hours to reach Berlin. Navigating these days wasn’t so easy for we didn’t have all these modern instruments, which by a few twiddles of a few knobs, turn out all the answers. All the way there I was kept hard at it plotting & guiding the aeroplane. We didn’t really see the city, the cloud spoilt the view but at the time I estimated we should be there the ack-ack started to burst up through the clouds. One run across and our bombs went away and believe me we didn’t stay around to see where they fell. The return trip wasn’t so pleasant, twice my navigation took us over heavily defended towns & twice we stoically suffered a pasting. That trip took 8 hours 15 minutes and it is the longest time I’ve been in the air.”

A mission to Brest nearly spelled disaster: “On one of the Brest trips [in December 1941] an odd thing happened. Just before we reached the target a photographic flare skipped off the rest couch and lodged in the control wires. The wild curving of our pilot, Sgt Williams, was our first indication that something was wrong. We then realised that the aeroplane was diving slowly earthwards in slow circles. It took two of us about 3 minutes to jerk that flare loose. Those days Brest was the harbour of the German battleships. Those below definitely took a dim view of any raiders that dared to approach, but we liked the place because there is only a narrow perimeter to pass over therefore the job was over in a few minutes.”

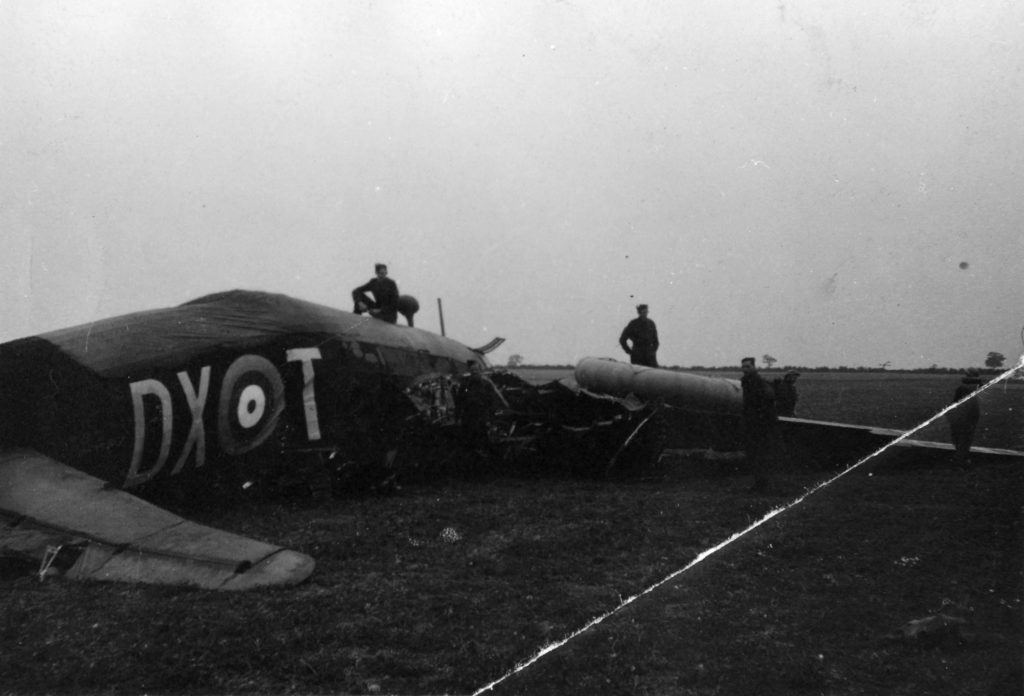

He describes his worst crash: “With our bomb bays full of 250lb, 500lb and 1000lb armour piercing bombs we roared down the runway on the first stage of our journey to Brest. The aircraft became airborne. That is when it evidently decided not to fly. We reached about 100 feet then the dear old lady settled down on its stomach again. Before the wreck eventually drew to a stand still, what was left of it, we had ploughed through about four fences, many ditches & three paddocks. No one will ever know why at least one of those bombs didn’t explode & why the aircraft didn’t burst aflame. Six air crew really scuttled that night. We shot out of any hole we could find & made for the nearest hedge & ditch. Next morning we took a photograph of the plane. Both engines had been ripped off, one wing was hanging loose, the bombs were scattered all over the place, and all the underparts had been torn away.”

Handwritten on the reverse: “We once piled up. I’m on the top of the aircraft.” Image: ALB1307613095

As war continued and the mission tally mounted, new aircraft were introduced. He writes: “The squadron converted to a new & more modern type of Wellington. We started operating again in March 1942. My 20th trip [actually his 17th, he counted wrong first time!] was a daylight job on Dusseldorf. A new type of navigation instrument called Gee came into being. It is an oblong box which when working, has a green dial. On this dial a navigator can work all sorts of miracles. On this day I used it for the first time operationally. The day was cloudy. The idea was that we should go to Dusseldorf staying in cloud continuously. We did by means of Gee. In the newspaper the Daily Mirror, we saw next day a few lines which stated that a solitary aircraft flew over western Germany. That was us.”

In the war history The Bomber Command War Diaries by Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt, it states for that day: “One Wellington on a cloud-cover raid to Essen [close to Dusseldorf] dropped its bombs somewhere in the Ruhr.”

Ironically, the following two days small operations were cancelled because of lack of cloud.

“We were first attacked by a German fighter on a trip to Lubeck. The Hun sneaked up on us from the rear. But fortunately our rear gunner got in with the first burst and scored a bulls eye. We all watched that fellow spiral seawards in a blazing dive.”

“I finished my first tour of 33 trips on the night of the 27th April 1942. Was I relieved. I was the 3rd Navigator to finish in 8 months.”

“By a bit of a wrangle I managed to get myself posted to 109 Squadron. This squadron was on a special job. They were dropping markers for the Pathfinder Force. Night after night we went and dropped these marker bombs on important targets. A marker, by the way is a bomb which bursts at a certain height above the ground and showers out bright candles. They can be green, red, yellow or a mixture of these colours. They fall & burn for approximately five minutes, in which time the bombers fly in and unload their heavy bombs on that spot.”

“An average Mosquito marking trip was as follows. We took off and climbed. Usually we operated at about 30 000 feet. Before we left the English coast we attained this height, then at a fixed time we shot off on our way. We started to use our special equipment about 10 minutes flying time away from the target. Once we started our bombing run we had to fly straight and level for the full 10 minutes. Although the enemy didn’t really discover until the end what we were doing he did put rows of heavy ack-ack guns up our runs. This of course, applies to the Ruhr targets, we went there so often. And when we were about four minutes away from the releasing point those gunners would let loose. It wasn’t fun. Quite often I had the thrill of flying through a hail of shells. They didn’t half kick up a shindy. On certain targets, such as Essen, we usually received a nasty pasting, the holes in the aircraft showed us how badly.”

“My first day Mosquito trip was as follows. [his 60th operation against the enemy to the Abeville area on 9 March 1944] We took off and flew to a prearranged position. Sometimes this was over the town of Reading. Once there we picked up a formation of 12 other Mosquitos. These tacked on behind us and we led them off on the raid. At a certain point we opened our bomb doors, they followed suit and when I released our bombs they let theirs go at the same moment.

Fighter Command supplied us with an escort of six Spitfires for these raids. These met us just at the French coast. On that first daylight trip of mine they arrived late, the first indication I had of their presence was when I looked to the rear & saw the angry looking guns, nose and spinning propeller of an aeroplane. For a moment I forgot it was the fighter escort and thought it an ME109 rushing in for the kill. I wasn’t half relieved when it banked away and showed its unmistakeable spitfire lines.”

“Many of our Mosquitoes were built to carry the ‘Cookie’ the 4000lb block buster. We took off carrying this huge bomb and with our special equipment we would lob it off into the middle of a town or factory.”

“When D-Day did arrive I had completed about 90 trips and about that time I was awarded the bar to my DFC.”

“Now let me go back to the buzz bombs. The dirty little rocket which only annoyed the harassed civilians. As we were going out on raids we would see them coming in spitting from their tails long streams of fiery sparks. When we were returning via southern England a buzz bomb would sizzle past us. Again and again the boys opened up the throttle of the Mosquito & had a race with them.”

“On the night of 7th August 1944 we were briefed for a raid on Caen. This was the focal point of the Beach head battle. We took off at 10 minutes to 10 and carried only one yellow marker bomb. The marker Mosquitos commenced the attack. Down dived our yellow markers. Visual markers then dropped green bombs on the correct spot. One thousand heavy aircraft then flew in dropping thousands of tons of high explosives on the small village.”

“That’s about all I have to say. It isn’t much, but the war is over and a memory is a convenient thing. I’ve had a lot of fun, excitement, many risky do’s and now there isn’t any war. Lots of luck. Wally.”

Without returning to New Zealand he was transferred to the RNZAF, but in July 1949 joined the RAF. He spent time instructing at No. 7 Advanced Flying Unit, the Empire Air Navigation School, No. 7 Navigation School and Headquarters of No. 63 Group.

He retired from the military in January 1958 to take up teaching in England.

Wallis Finlay’s collection was donated in 2013 and among the items are numerous letters he wrote to his family in New Zealand. In late 2024 his extended family gathered in Christchurch for a family reunion. They visited the Air Force Museum and this blog is adapted from the presentation put together for the younger generations of the family who were interested to learn about his wartime exploits.