Eighty-five years on, we remember one of the New Zealand aircrew who defended the skies over southern England during the long hot summer of 1940. Nearly 130 New Zealanders took part in the Battle of Britain in 1940, and 20 were killed.

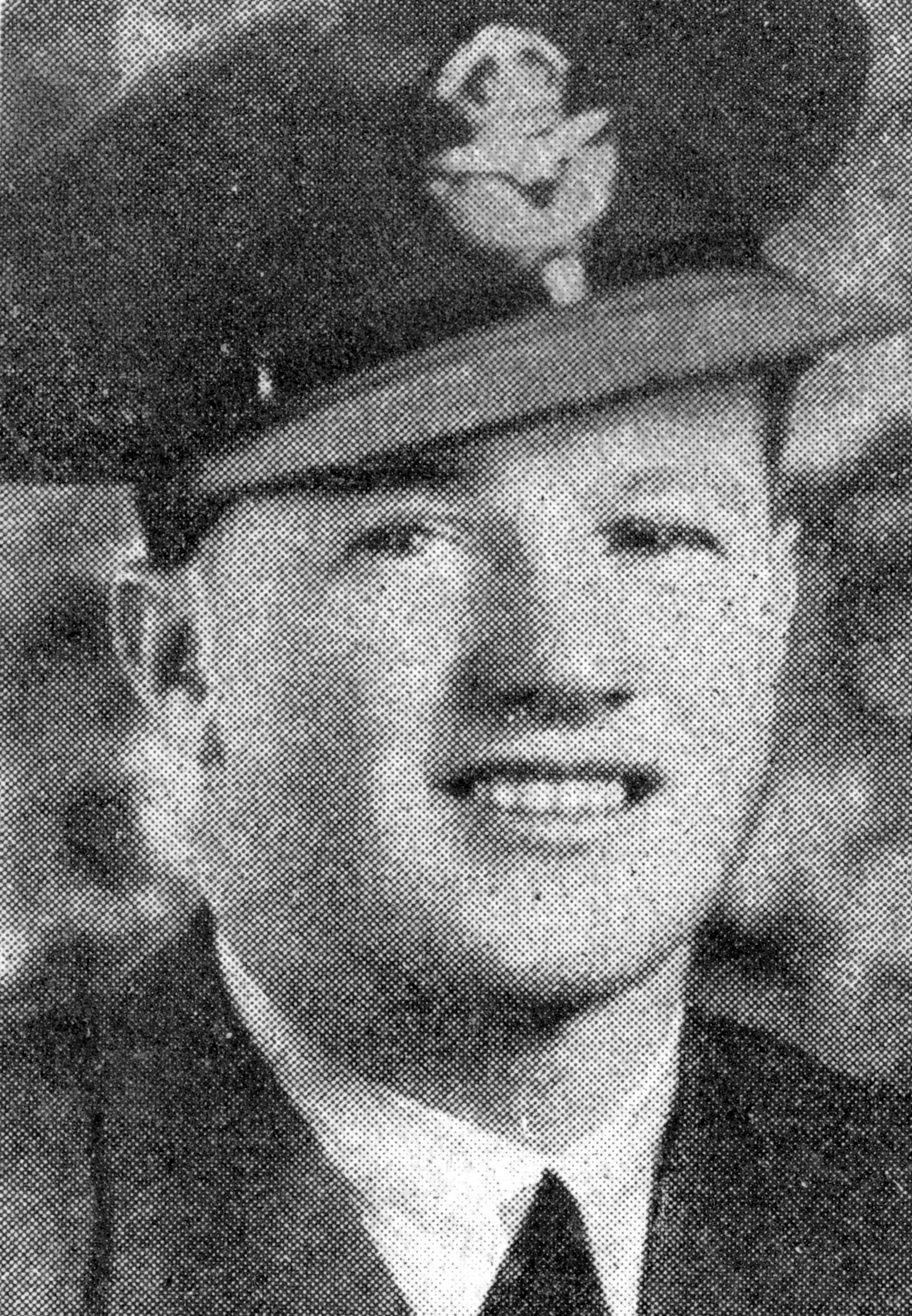

Like many others, one young pilot was thrown into the midst of this desperate battle. His name was Charles Stewart and he came from Wellington.

He was born on 22 November 1922 and attended Wellington College, where he was a respected boxer. Ater school he got a job as a clerk at Dyes and Chemicals Limited in Wellington.

To war

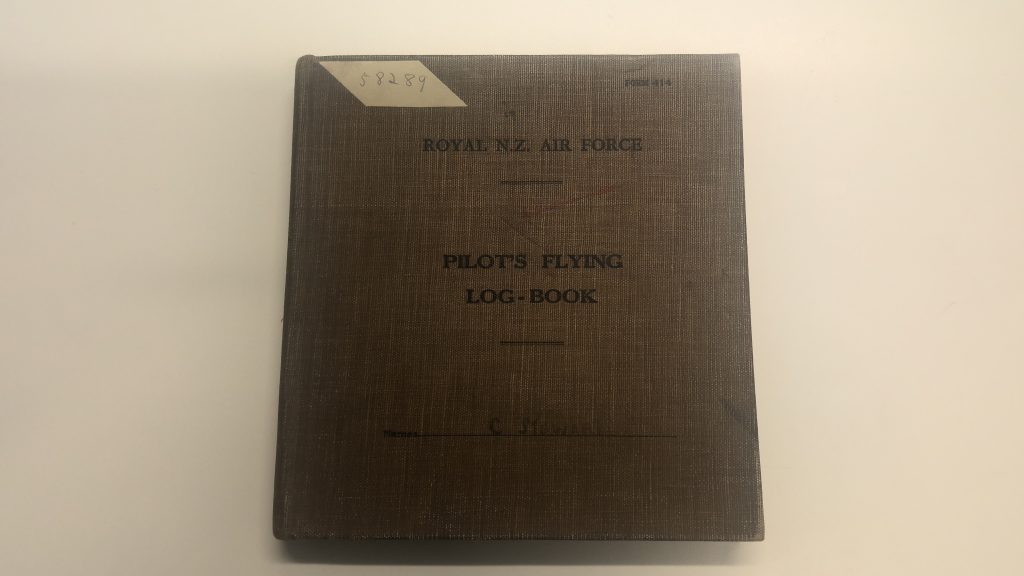

When war broke out, Charles was selected to go to Britain and received a Short Service Commission with the Royal Air Force, after a course of flying instruction at No. 1 Elementary Flying Training Squadron at Taieri, near Dunedin beginning in October 1939. He received his pilot’s badge on 6 April 1940 and set sail for Britain on the RMS Rangitata, arriving on 20 July 1940, just after the Battle of Britain had started.

Pilots were already in short supply and so novices like Charlie (as he was now known) did not get the usual depth of training.

He was posted to No. 7 Operational Training Unit at Hawarden in Wales to learn how to fly Spitfires.

Less than three week later he was posted to No. 54 Squadron on 21 August 1940. On arrival he and fellow New Zealander Mick Shand arrived at Hornchurch and were introduced to the indestructible New Zealander Alan Deere.

Deere took Shand into his flight and asked the pair about the training they had had. Shand replied:

”I’ve got a total of 140 hours approximately, mostly on Wapitis. I only managed to get 20 hours on Spitfires at O.C.U and it was hardly enough to get the feeling of flying again after a two month lay-off. As a matter of fact, I know damned all about fighters, I was trained as a light bomber pilot.”

Charlie Stewart was not much better off with a mere 26 hours on Spitfires. He ended up in B Flight under the command of Englishman Flight Lieutenant Dorian Gribble DFC.

Despite this, within three days, he was flying his first patrols. On 24 August he flew three short patrols, but just 15 minutes into the patrol, at 3.45 pm came under friendly British anti-aircraft fire over the coast, which hit his Spitfire. Charlie bailed out and descended by parachute into the English Channel. His aircraft crashed in Kingsdown. Charlie later casually recorded in his logbook ‘Shot by Ac.Ac. Landed in Channel by ‘chute’.

After 15 minutes he saw an Air Sea Rescue launch but it failed to spot him and turned away. Stewart later described this as one of the worst moments of his life. Another launch appeared in 45 minutes and picked him up.

As the craft neared Dover, it was machine-gunned by a Me109 but without damage. Stewart was admitted to Canterbury Hospital suffering from shock and exposure. The following day, Mick Shand was shot up by BF.109 fighters and wounded and joined Charlie in hospital.

North and South

By the time Charlie rejoined the Squadron on 15 September, they were having a well-earned rest at Catterick in North Yorkshire.

Here they patrolled the North-East coast of England and Charlie was finally able to get some good training and experience on the Spitfire.

On October 1, Charlie joined No. 222 Squadron at Hornchurch, again in B Flight under Flight Lieutenant Andrew Robinson. His logbook reveals little about events during this period, except constant patrols, two or three times a day each lasting about an hour to an hour and a half, which must have been very tiring.

Finally on 15 November the squadron was pulled back to RAF Coltishall and No. 12 Group in the Midlands. That very day, Charlie crashed his Spitfire, without injury.

Disaster struck on landing again the following day, when he was slowly landing without engine power and opened up the throttle, which stalled the engine. He struck the ground in a semi-stalled condition and the undercarriage collapsed. The Base Commander at Coltishall considered the crash to be Charlie’s fault, handing him a very negative red endorsement in his logbook. This was later expunged by higher authority in No. 12 Group.

Patrols continued for the rest of the year, including one on 17 December where he ‘chased Junkers’.

The New Zealand Spitfire Squadron

On 14 March 1941, Charlie was posted to No. 485 (NZ) Squadron, working up at RAF Driffield, thereby being a foundation member. The routine of patrols, training and occasionally escort work continued but in June 1941, the squadron started to conduct sweeps of the French Coast, known as Circuses. On his third sweep, recorded having ‘collided in mid-air with P/O Barratt’. Thankfully, both pilots made it home.

After several days escorting bombers, on 8 July 1941, Charlie was providing coastal cover for a raid with three other Spitfires, he encountered what he thought were three Spitfires. His Combat Report later admitted his mistake:

“They were flying towards me and at first I thought they were Spits. They had duck-egg blue spinners, the same as our machines. Just as they were about to pass under me I saw the crosses on the wings. They were ME. 109s. I did a starboard turn and gave one a squirt at about 100 yards. He went into a dive and I followed him down, giving him a couple more bursts. We were getting near the sea so I pulled out. It was a bit hazy and I came out only just in time as I got down to within thirty feet of the water. The Jerry didn’t stop. He went straight into it and I saw a great burst of foam.”

Luck runs out

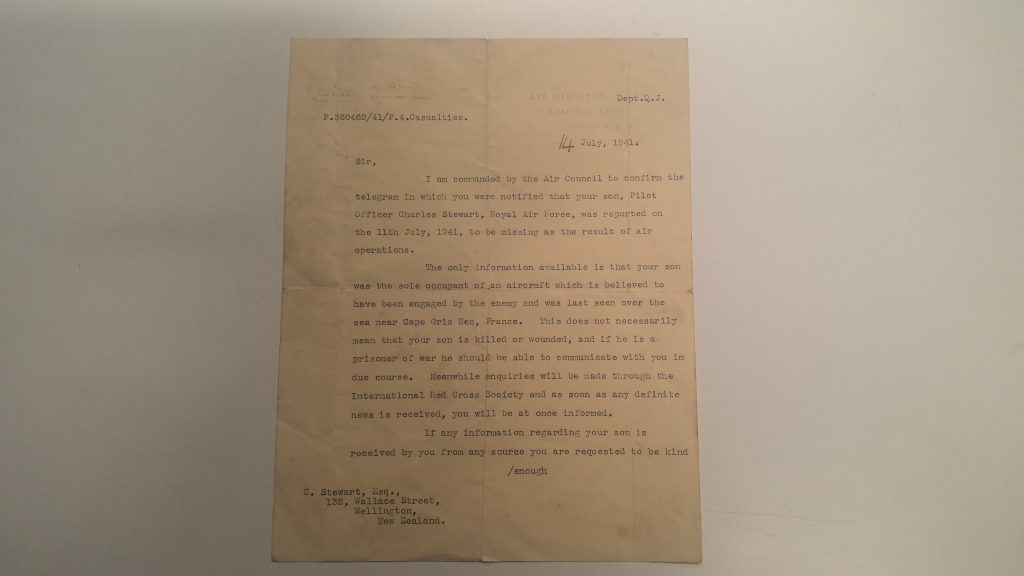

Charlie’s success was short-lived. Just days later, on 11 July 1941 he was part of a sweep of 12 Spitfires over the French coast. They were attacked by enemy fighters. He was last seen over Cape Gris Nez, but his fate remains unknown.

Charlie’s mother received a letter from the Air Ministry saying he still might be a prisoner, but it was a vain hope. Ultimately, he would be commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial to the missing in Surrey.

The family would also be revisited by tragedy. Charlie’s brother Daniel has also joined the RNZAF as a member of the Aerodrome Construction Squadron.

He survived the fall of Singapore in 1942 and was evacuated to Australia via Java. While in Australia, he was fatally injured in a motor vehicle accident on Friday 13 March 1942 at Heathcote in Victoria, where he is buried.

Epilogue

No veterans of the Battle of Britain are still alive, but their memory lives on. Of the 2937 men who took part 544 lost their lives in the Battle. A further 795, like Charlie, were lost by 1945.