Sliding open my wardrobe door, and wading through drawers of clothes I find myself making that cliché comment, “I have nothing to wear, I need to go shopping”. This is usually followed by guilt, as actually I am really lucky to have a range of clothes, say, compared to my Nana who lived during World War Two. It also makes me wonder how she would view our fast fashion culture today? Even though it was hard back then, perhaps we can draw some inspiration from this era.

During World War Two it became increasingly difficult for New Zealand to import material, especially after Japan entered the War in December 1941, making the seas around us dangerous with their heavily-armed ships. At the same time, many factories were diverted to produce items for the War Effort – not only to supply our own forces but also for Britain. The system of rationing was introduced, both here and overseas, to ensure there were enough goods to go round and that distribution was fair.

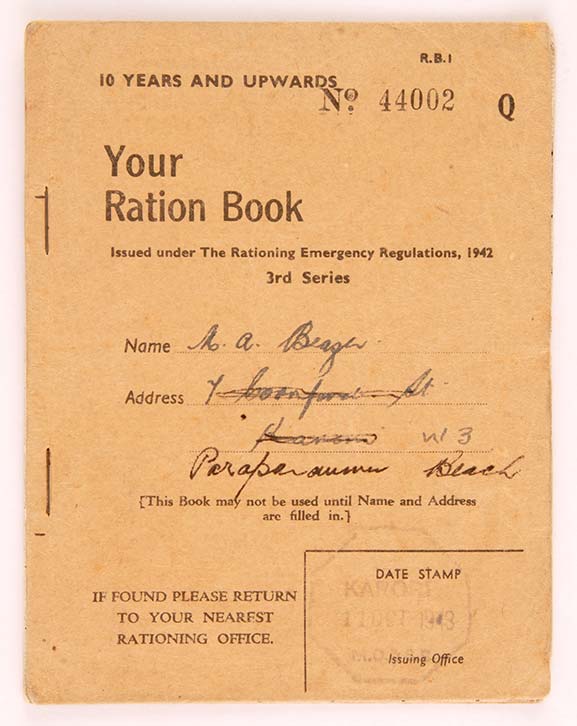

In New Zealand, the first garment to be rationed was the silk stocking. This was followed by footwear, clothing, and material in May 1942. As clothing became scarce, New Zealanders started to economise by carefully planning their clothing purchases.

Related to rationing were the austerity clothing measures introduced by the government. These regulations were designed to reduce the amount of fabric used as well as the time it took companies to manufacture garments. The number of pleats, seams, and buttonholes were fixed, as well as the widths of sleeves, hems, and collars. Embellishments such as embroidery and appliqué work were banned, pockets were limited and trouser turn-ups were prohibited. The results of this can be found in the iconic style of 1940s fashion, where silhouettes are simple in style, practical, refined and unadorned, with boxy, square shoulders.

Fashion designers of the time had to allow for these changes by reducing the amount of material in their garments. Magazines like Vogue started to advise alternatives such as dressing up the same suit with different scarves and blouses to create diverse looks. They even suggested replacing items such as stockings with a cream, advertised as “so incredibly real in its likeness to the sheerest, most luxurious stocking that only touch can reveal the illusion!”

So with all the shortages, rationing, and finally, boundaries, restricting what they could buy – what did people do? They got creative!

Back then it was common to create your own clothes, as it was usually cheaper than purchasing ready-made. So Kiwis took their sewing skills to the next level by using their ‘No. 8 wire’ mentality to prolong the life of clothes though mending and patching, reusing materials and re-hashing garments.

Fast-forward 76 years and our clothing landscape looks really different. The world’s fashion capitals present the season’s trends, which chain stores and mass retailers then adapt for men and women on the street. As consumers, we are convinced that our current wardrobe stocks are not fashionable, so we buy new. In comparison to the 1940s, our fast fashion culture is possible because the market can supply the demand, clothes are relatively cheaper and, with our busy lifestyles, we are more time-poor and perhaps lack the skills to create our own anyway.

But fast fashion comes at a cost and for me, this is something that adds to the feeling of guilt right after I exclaim, “I have nothing to wear, I need to go shopping.” As more people buy clothes and don’t keep them as long as they used to, more products are made at a faster pace, with the aim of reducing manufacturing costs as much as possible. This in turn has negative effects on the environment, as more materials, water, chemicals, and modes of transport are used in the manufacturing process. From an ethical point of view, I also think about the less than ideal working conditions many people are subjected to while sewing this year’s trending garment together.

Another thing that adds to my guilt is polyester. This common fabric, when washed, sheds microfibres. These small pieces of plastic, pass easily through our wastewater treatment plants and add to the plastic in our oceans. Plankton eats the plastic, and up it goes in the food chain. So not only are we contributing to climate change, land degradation and social inequality but we are also adding to (in miniature form) the floating plastic islands in our oceans.

So what can we do? Perhaps concepts from my Nana’s era would be able to help us curb our appetite for fast fashion to something more sustainable. What do think?