Among the thousands of objects in our collection are some which have amazing stories behind them – ripping yarns’ even! We share some of these objects and stories in a rotating display within our ‘Horizon to Horizon’ gallery at the Museum, but we’ll also share the latest ones here on our blog.

John ‘Jack’ Green – West Africa

Warrant Officer John ‘Jack’ Green, from Northland, was an air gunner with No. 490 (NZ) Squadron RAF, a Coastal Command unit based at Jui, Sierra Leone. Crews formed in Scotland, where they trained on Short Sunderlands before making their way to West Africa. Jack and his nine crew mates duly set off for Jui in July 1944, having taken possession of a new aircraft just a few weeks earlier.

On the final leg to Sierra Leone, the Sunderland developed engine trouble and the crew had to ditch off the coast of Senegal. They bailed out into dinghies, coming ashore – in the dark – several hours later.

All ten were lucky to escape without injury, however, their aircraft and belongings were lost. Jack was left with only his shorts, his life preserver, and a leather belt, but he observed that “…I still have myself, and that is the main thing.”

On the beach, the crew made contact with a small group of locals who were patrolling the coastline, before being spied by another Sunderland. They were subsequently picked up by the Free French Navy corvette Lobelia and given clothes, food, and beds.

Eventually arriving in Jui, the crew were assigned a spare Sunderland with the letter code ‘Q’. The cantankerous Q ‘for Queenie’ proceeded to test their nerves on a regular basis, treating them to two more ditchings over the following seven months.

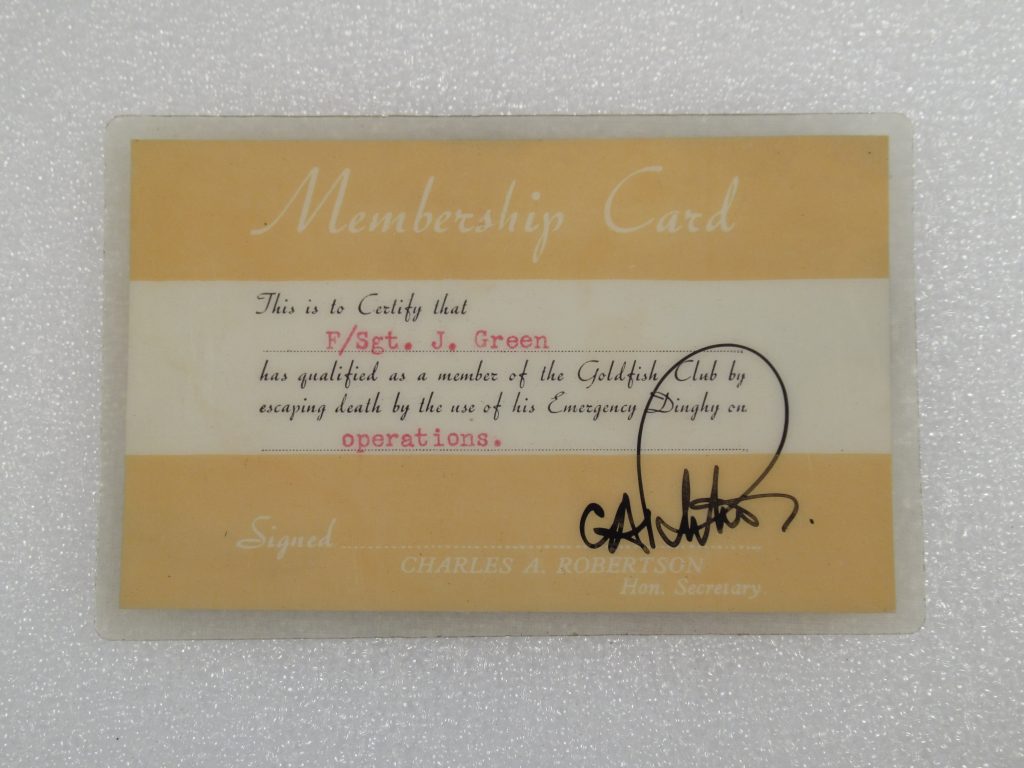

The experience on the way to Sierra Leone qualified Jack and his crew mates to join the Goldfish Club, the association of air crew who have parachuted or crashed into water and survived because of a floatation device.

Neville James Mundell – Europe

As World War Two entered its final stages, inmates of German prisoner of war camps became increasingly reliant on Red Cross parcels for anything more than the most basic and meagre of food rations.

Barter systems were common. At Stalag Luft III, in German-occupied Poland, Flight Lieutenant Neville Mundell and several of his fellow prisoners made golf balls to trade for chocolate, which Neville described as ‘a lifesaver.’

Materials were limited and the prisoners had to be resourceful. To make the balls, they fashioned leather outers from the tongues of their prison-issue boots and stuffed them with shredded rubber salvaged from the soles of tennis shoes. Strands of cotton from their underwear were twisted together and waxed with candle grease to make thread, and the ball was sewn up like a baseball. Neville and his colleagues also made golf clubs, pouring the molten metal of old food cans into sand moulds to make heads, and attaching them to shafts made from piano legs or bed slats.

By Neville’s account, the balls were great, and bounced well. Scratch marks on this ball tell the story of when Neville hit it into the camp’s barbed wire. The ball fell into no-man’s-land, which meant Neville had to ask the German guards if he could retrieve it: “…they gave permission but kept their guns trained on me until I was back behind the wire.”

When the camp was abandoned, the prisoners were ordered to collect as many of their belongings as they could carry before being marched out. Neville took this golf ball with him.

Jim Sheehan – Afghanistan

During his 2011 deployment to Bamiyan, Jim Sheehan bought this pressure cooker at the local bazaar and sent it home in the mail. It’s a smaller version of pressure cookers bought by the New Zealand base (Kiwi Base) cook Staff Sergeant ‘Spanner’ Wilkinson to make meals in the mess. By all accounts, these meals were worth writing home about.

Getting food to Kiwi Base wasn’t always straightforward. Being in the central mountainous area of Afghanistan, food was transported from the capital Kabul by truck, or by helicopter when the pass was snowed in. The food truck was driven by a local, who on one occasion arrived very shaken, with bullet holes in the back of his vehicle. Fortunately, the only casualty was a box of paper towels.

Despite the challenges, Spanner’s food was so highly rated that it drew visitors to Kiwi Base. Jim recalls one winter’s day waiting for a Chinook helicopter to arrive with mail from Bagram. Unexpectedly, American soldiers started piling off, having caught the flight just to so they could eat in the Kiwi Base mess. With all those visitors on board there was no room for the mail the Kiwis had already been waiting a month for.

The Christmas Dinner at Kiwi Base was one to remember. They feasted on steamed trout and lobster – and were supposed to have t-bone steaks, but they were so tough that they went into the pressure cookers for Spanner’s famous curry. Despite receiving a phone call from the ‘powers that be’ wanting an explanation for the amount he’d spent, Spanner said it was all above board – he’d been crafty with his budget throughout the year and saved up for the special occasion.

Jack Joll – Germany

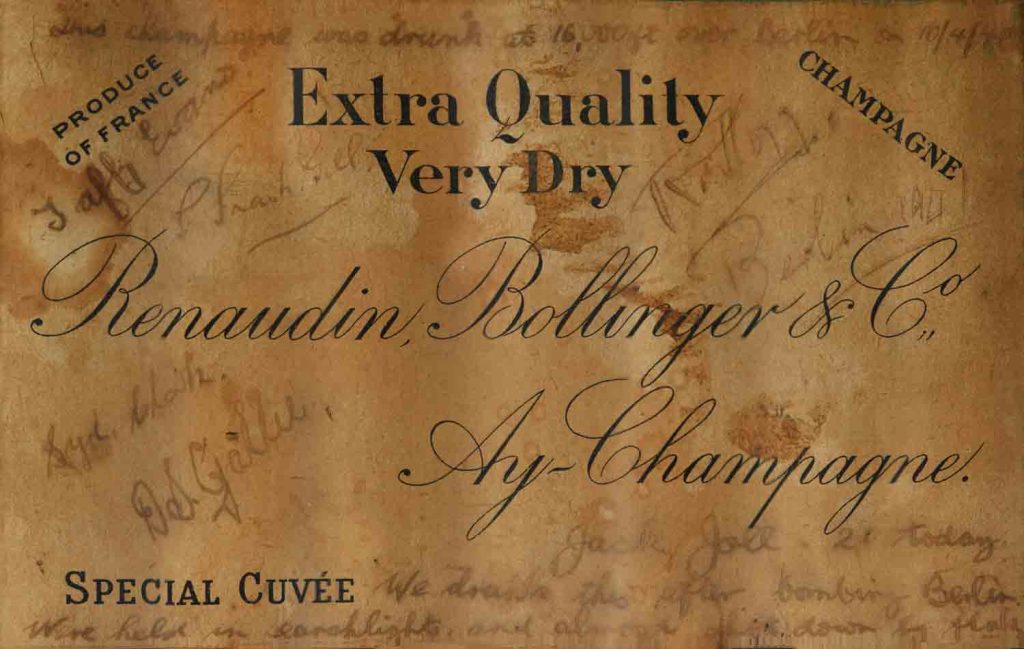

The night of 9 April 1941 was one like many others for the members of No. 75 (NZ) Squadron RAF, with another raid over Berlin. This night, however, would be particularly memorable for one Kiwi pilot. Unbeknown to Sergeant (later Squadron Leader) Jack Joll, his crew were carrying a secret cargo, a surprise to mark a very special day in the young airman’s life.

In the air over Berlin, Jack celebrated his 21st birthday in a very unique way. His crew, comprising two fellow New Zealanders and three British members, had arranged to smuggle this bottle from the famous Bollinger Champagne house onto the aircraft. After the fall of France and the occupation of the Champagne region, by Germany the iconic sparkling wine became a rare commodity. This demi (half) bottle would have been of considerable value.

Kept safe through the flight and the rattle of flak (anti-aircraft fire) over their target, the crew presented it to Jack shortly after dropping their bombs and turning for home. Popping the cork as they flew home, Jack and the crew all shared a drink from the bottle before inscribing their names on the label. The only indication of the danger faced on a near nightly basis by the members of RAF Bomber Command being an almost offhand comment written along the bottom of the label; “caught in search lights and nearly downed by flak”.

Gordon Woodroofe – Europe

Warrant Officer Gordon ‘Woody’ Woodroofe was captured as a prisoner of war (POW) by the Germans after his Wellington bomber ditched in the North Sea in September 1941. While imprisoned, Gordon swapped identities with an Australian soldier. He was transferred to another camp, and in May 1943, escaped from a komando (working party), making it to the Austrian alps before being recaptured.

Undeterred, Gordon began to prepare for another escape. He became a successful gambler, winning thousands of cigarettes, which had huge tradeable value, by playing a dice game – “I told no one the purpose of acquiring cigarettes other than to say I needed them to purchase items for an escape”.

Gordon had been given a pair of civilian shoes, so his first investment was 400 cigarettes to get the soles repaired. He also acquired a beret, shirt, tie, coat, and trousers to disguise himself as a French civilian.

Gordon escaped from another kommando in August 1944, travelling by train through northwest Germany to the Baltic port of Wismar, where he was assisted by a group of Frenchmen to board a Swedish coal vessel. When the ship docked in neutral Sweden, Gordon made his way to the nearest police station, and after receiving a new passport, was conducted to the British Consulate in Stockholm. He was flown back to Scotland on 8 September 1944.

Gordon was the only New Zealander to successfully escape from a German POW camp and score a ‘home run’ back to Britain, and one of only 34 RAF POWs (out of 10,000) to achieve the same. For his efforts, Gordon later received the Military Medal.