Re-reading the RAF: cultural imaginings of the flyer

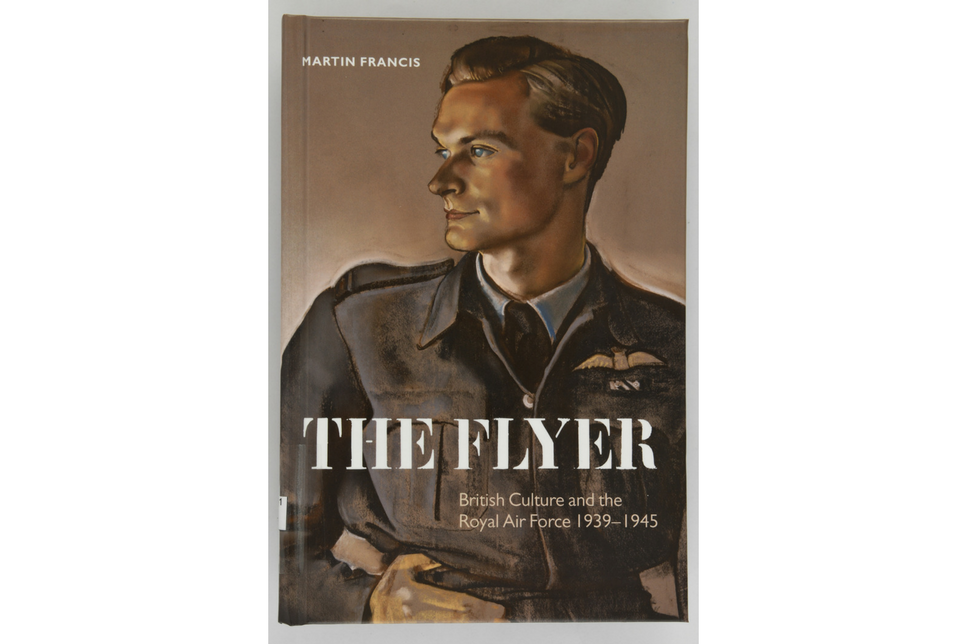

The flyer – dashing youth, fortune hunter, chivalrous adventurer, city destroyer and defender. Given the popular appeal and significant wartime role of the RAF flyer between 1939 and 1945, it is perhaps surprising that until the publication of The Flyer: British Culture and the Royal Air Force 1939-1945 in 2008, no extensive or scholarly study of this subject had been produced. Scholarly studies of the wartime RAF tended to be works of military history, focussed on operations, while popular history accounts concentrate on squadrons, aircraft types and individual biographies.

The author, Martin Francis, is Professor of War and History at the University of Sussex. His study examines how the flyer persona was represented in British culture during the war, but also how flyers ‘represented themselves and made sense of their lived experience.’ [1] As a work of cultural and social history, the book uses the ‘lives and representations of RAF flying personnel to illuminate much broader issues of gender, social class, national and racial identities, emotional life, and the creation of national myth in twentieth-century Britain.’ [2]

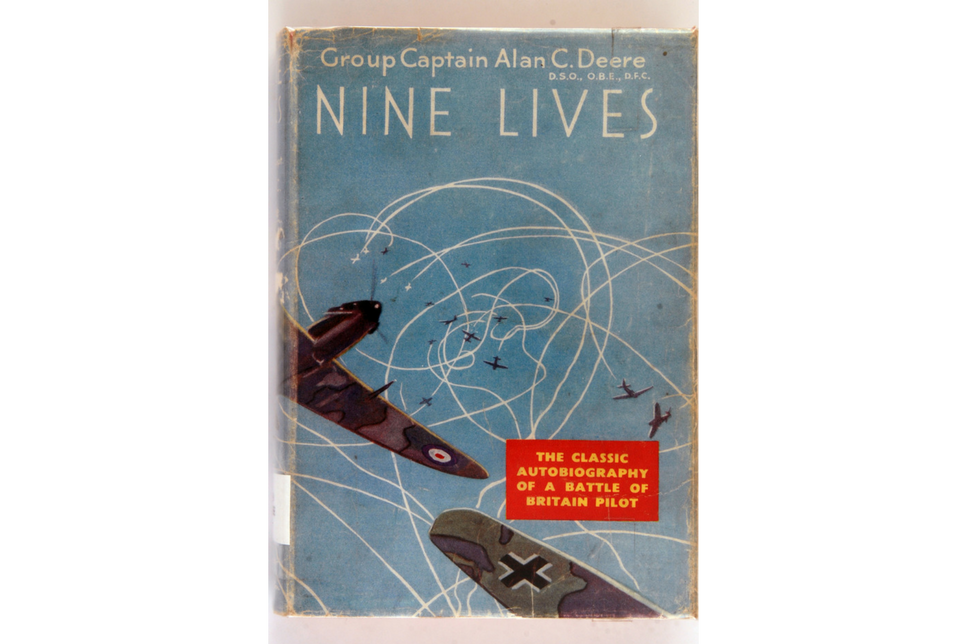

Memoirs, novels, films, plays, poems and broadcasts are all used as historical sources, including Kiwi Battle of Britain pilot Alan Deere’s autobiography, Nine Lives (1959). This wide-ranging selection of sources – especially the inclusion of literary and cinematic texts – allows Francis to demonstrate the ‘mediation’ of this popular image of the RAF flyer within British culture at the time of the war. Eight chapters cover the various guises of the RAF flyer: “The Allure of the Flyer”; “A Man’s World”; “The Flyer in Love”; “Husbands and Fathers”; “The Flyer and Fear”; “A Darker Blue “; “The New Achilles? Literature, Technology, and Violence”; and “Coming Home”

The flyer and masculinity

Francis argues that RAF flyers embodied British wartime masculinity, but that the flyer’s relationship to the personal, physical, and psychological effects of flying combat missions (individual loss, disability, disfigurement, psychological breakdown etc.) reveals the ambiguities and contradictions at play within Second World War masculinity. As this work shows, the contrasts of daily life for wartime aircrew were extreme. For British airmen, many of whom were based on home soil, daily routine shifted between the domestic life of family and the high stakes, and at times macabre world of operational flying.

However, male and female experiences of the war were not opposing, but rather interrelated – the existing institutional culture of the RAF (and of British masculinity itself) was constantly negotiated and renegotiated by changes occurring across British society as a whole, and how the nation saw itself in relation to the rest of the modern world. While only focussed on flying personnel – the RAF fighter boys and bomber boys – Francis’s study offers a fresh, gendered perspective on the social impact and legacy of the RAF, an institution forever connected to Aotearoa and the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF).

Image from the collection of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

The New Zealand connection

10,590 New Zealanders served with the RAF in World War Two, sustaining 3,285 fatalities. [3] Some, like Desmond James Scott, served as Commanding Officers at RAF Stations; Keith Park commanded the whole of No. 11 Group, and by the end of October 1940, half of New Zealand’s pilots were under his command. [4]

New Zealand airmen in the RAF fought in every theatre of war, with 90 percent of New Zealand airmen spread throughout the RAF squadrons. In April 1940, the first of the New Zealand squadrons – No. 75 (NZ) Squadron – was formed, becoming a precedent for other Dominion-identified squadrons; yet only 10 percent of New Zealand airmen would fly in the seven designated New Zealand squadrons. [5]

New Zealanders were consequently enmeshed in the life and culture of the RAF. New Zealanders serving in the RAF were part of a military service culture unique to the RAF, which in turn was influenced by and helped to shape British culture in the twentieth century.

Our Reading Room is open to the public by appointment. Please contact the Research Team at research@airforcemuseum.co.nz to book your visit.

References

[1] Martin Francis, The Flyer: British Culture and the Royal Air Force 1939-1945, Oxford University Press (New York) 2008, p.8

[2] Francis, The Flyer, p.3

[3] Margaret McClure, Fighting Spirit: 75 years of the RNZAF, Random House (Auckland) 2012, p.89

[4] McClure, Fighting Spirit, p.68