The entry of Japan into the Second World War in December 1941 led to the creation of a number of short-lived squadrons to fill the immediate defensive needs of New Zealand and train personnel for future operations of the RNZAF against the Japanese in the Pacific. These are the stories of two of these squadrons, which are closely linked together.

No. 7 (GR) Squadron, Waipapakauri

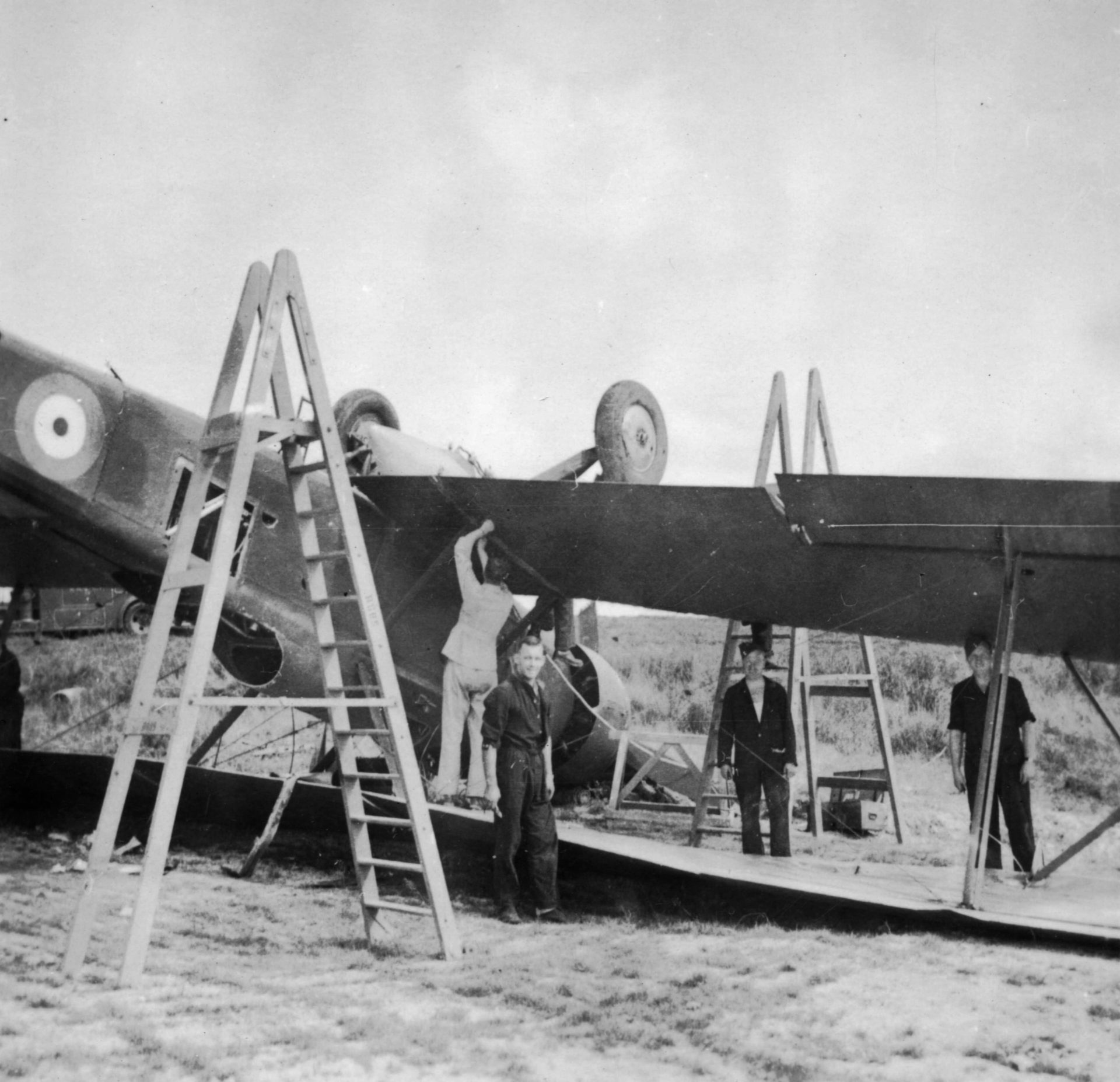

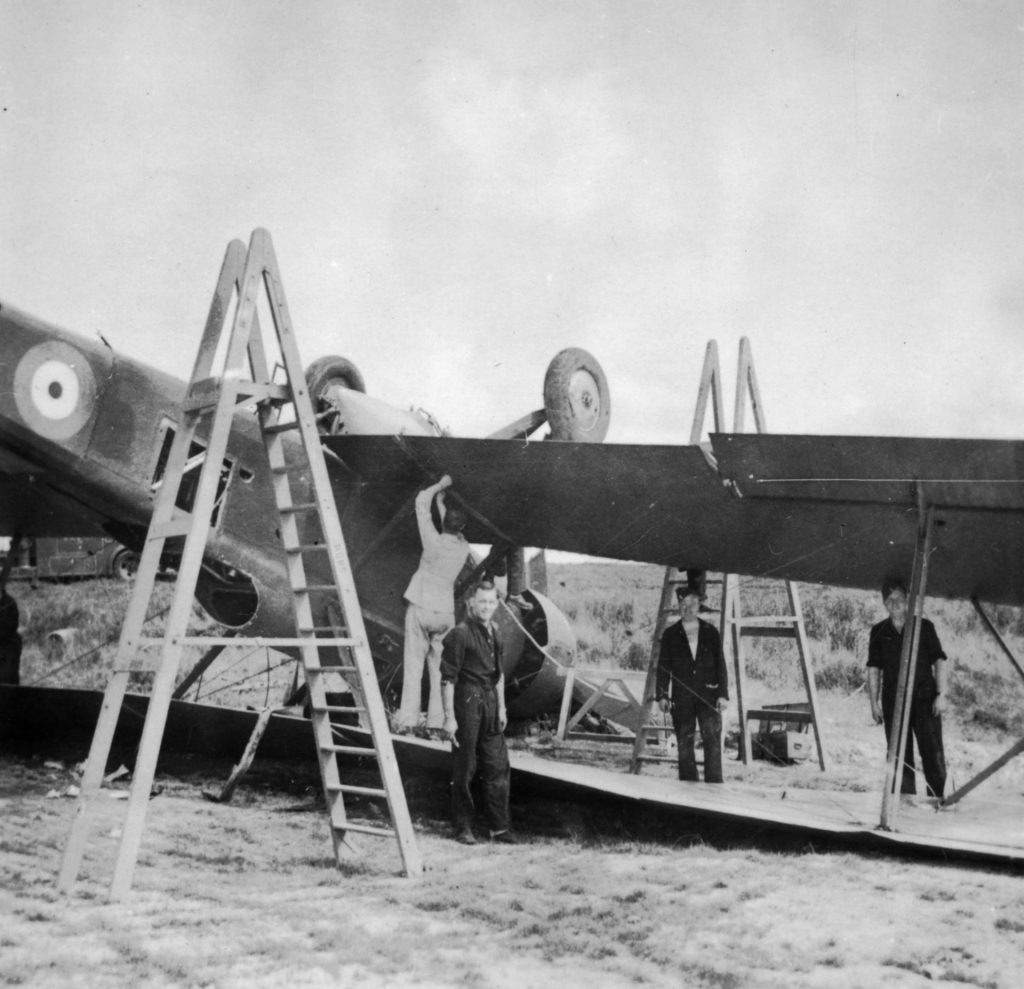

No. 7 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron came into being on 10 February 1942 at RNZAF Station Waipapakauri in Northland. It was an offshoot of No. 1 Squadron, which had operated a detached unit of Vickers Vildebeest/Vincent aircraft from the airfield, maintaining anti-submarine and shipping escort operations.

The first commanding officer of No. 7 Squadron was Squadron Leader Alfred Turner, a former airline pilot of great experience. By February 1942, the Squadron had 13 Vildebeests or Vincents on charge, plus one Tiger Moth.

The first operation flown by the Squadron should have taken place on 10 March 1942, but the patrol by three Vildebeests was cancelled due to bad weather. After this inauspicious start, there was more bad luck. Vildebeest NZ124 landed heavily on 12 March and ran into parked Vildebeest NZ137. No one was injured, but NZ124 was written off. Four days later, another Vildebeest was damaged in an accident during gunnery training.

Despite these setbacks, operations finally commenced on 5 April 1942 with three Vildebeest sorties successfully escorting a naval convoy. From this period on, No. 7 Squadron routinely provided convoy escort or anti-submarine patrols in New Zealand’s northern waters.

In addition to the operations constantly taking place, normal life at Waipapakauri continued. In July 1942, the Squadron celebrated the marriage of Flying Officer H.N. James to Joan O’Toole at Ōtāhuhu church. In August 1942, a new officers’ mess was opened.

On 30 October 1942, tragedy struck. Vildebeest NZ1222 piloted by Pilot Officer G. Gunn was on convoy patrol. It failed to meet the ships and was recalled, but nothing more was heard and it was assumed lost at sea. As well as Gunn, Pilot Officer S.G. Bromley (observer) and Pilot Officer R. Dent (wireless operator) lost their lives.

1943 opened with another accident to a Vildebeest, NZ126 rolling into a ditch with brake failure. Operationally, great excitement occurred on 26 February 1943 when a submarine was reported in two consecutive locations off Tauranga. Four Vildebeests and a Vincent were sent to Bay of Plenty but failed to locate any sign of an intruder.

At the end of May 1943, the Squadron learned of their imminent disbandment in a memo: “No. 7 Squadron will disband forthwith, as Vincents forming its equipment have now been declared obsolete for operational duties. Most of its aircraft will be transferred to No. 8 Squadron as will four of its most experienced crews”.

No. 8 Squadron, Gisborne

In early 1942, the East Coast of the North Island had little air protection. To remedy this, in April 1942 the nucleus of a new General Reconnaissance (GR) squadron formed at Whenuapai under the command of Squadron Leader C.L. Monckton and the following month, an advanced party arrived in Gisborne. Two Vildebeests and eight Vincents arrived shortly after from other units. One of the Vildebeests on strength was NZ102, currently under restoration at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand as the last surviving Vildebeest in the world.

Operations commenced in June 1942 working with No. 1 (GR) Squadron based at Nelson, protecting shipping along the East Coast of the North Island bound to and from Wellington.

The accommodation and layout of the hastily conceived Station ensured that everything was dispersed around four camps and the personnel were trucked in daily. Living conditions were primitive. Wally Ingham was serving as ground crew that first winter, and recalled it was something of an ordeal:

“Tremendously cold nights with apparently endless rain coupled with draughty huts, many of which leaked, no lights or heating of any kind, no hot water, caused a wave [of] discontent among the airmen who were repeatedly soaking wet and generally unhappy with the condition prevailing. Their only consolation being their contacts with the good citizens of Gisborne.”

In contrast, the officers of the Squadron occupied a requisitioned mansion called “Sandown”, about a mile from the aerodrome.

One of the odd things about operations by No. 8 Squadron at Gisborne was that the New Zealand Railways department had laid track across the aerodrome, so a traffic light system had to be employed to ensure trains and aircraft were not in the same place at the same time!

The end of 1942 saw No. 8 Squadron also lose an aircraft in tragic circumstances. On 8 December 1942, Vincent NZ332 took off on patrol and was never heard from again. Pilot Flying Officer Peter Kinder, navigator Flying Officer C.M. Turnbull and Sergeant Nepia Stuart were missing.

Searches over the next few days failed to reveal the fate of the aircraft. The loss was particularly sad as Kinder had survived the Fall of Singapore and returned safely to New Zealand almost exactly a year before.

Losses such as these, and the arrival of more modern aircraft for maritime patrol work, such as the Lockheed Hudson and (later) Ventura, meant that the Vildebeests and Vincents would be slowly phased out.

In fact, on 4 May 1943, the GR Squadrons were instructed that the two types were not to fly beyond gliding distance from shore to avoid similar tragedies. This effectively made No. 8 Squadron non-operational and most of the aircraft were sent to Ohakea to await disposal. Plans were already in place for a new role for the Squadron.

While the remnant of the unit remained at Gisborne, several personnel were sent to the United States to become familiar with the Grumman TBF Avenger. Later in 1943, No. 8 Squadron ceased to exist, and No. 30 Squadron and No. 30 Servicing Unit RNZAF (later joined by No. 31 Squadron) were formed at Gisborne and began preparing to take their Avengers to war in the Pacific.