When it comes to caring for our collection, we collections technicians have the same fundamental job – to process objects after they join the Museum’s collection and provide for their ongoing care. This includes ensuring the information about them is properly recorded and searchable in our database, and that they are stored safely and securely, thereby preserving them for future generations. This is front of mind as we work through our current cataloguing project.

But, the range of material we receive (archival, textile, etc.) requires us to focus on different aspects of the same overall process. How does our approach differ depending on the kind of object we are dealing with? In this blog, our archives and collections technicians, Louisa and Murray, highlight the key differences in our mahi (work), from cataloguing through to housing and storage.

Numbering and arrangement

Louisa:

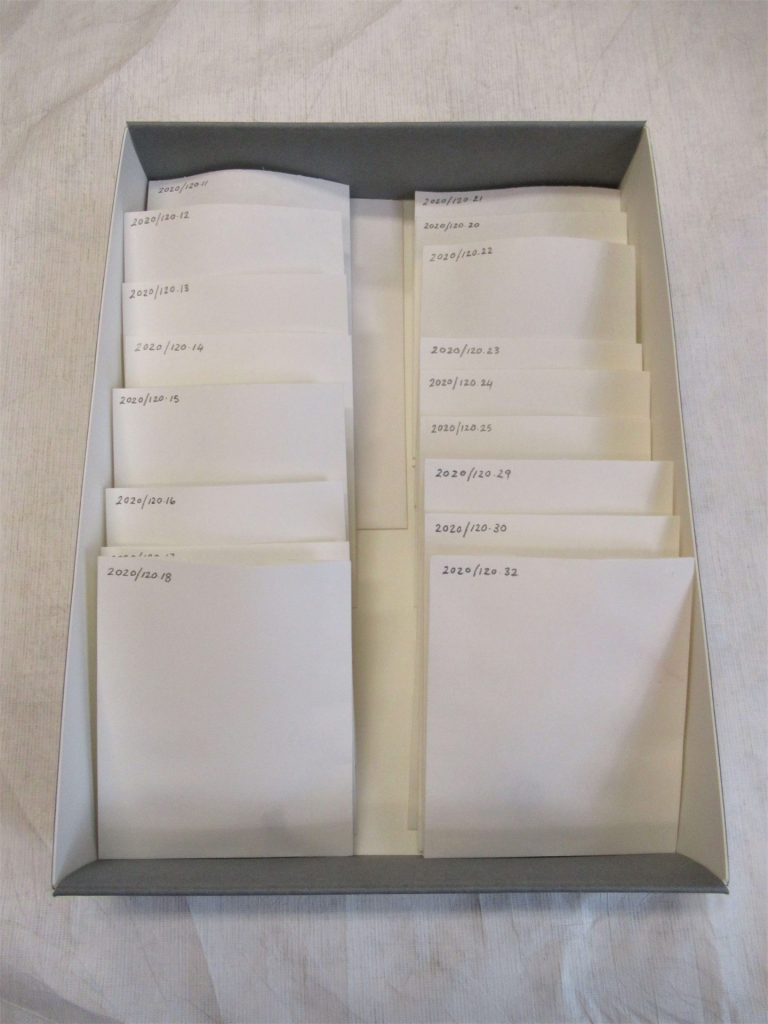

When new objects are added to the collection by the Museum’s Registrar in a process known as ‘accessioning’, the first step is to order and number them. This is so that each individual item has its own unique identifying number and the records are arranged in a logical series – physically and digitally, in our Vernon Collection Management System (CMS), Vernon. For archival (paper-based) collections, this is usually done by date; however, the principle of original order is also applied. This is vital, as researchers need to navigate records easily, so they can find specific information. If flying log books are present, these important records always take priority position in the archival series.

Murray:

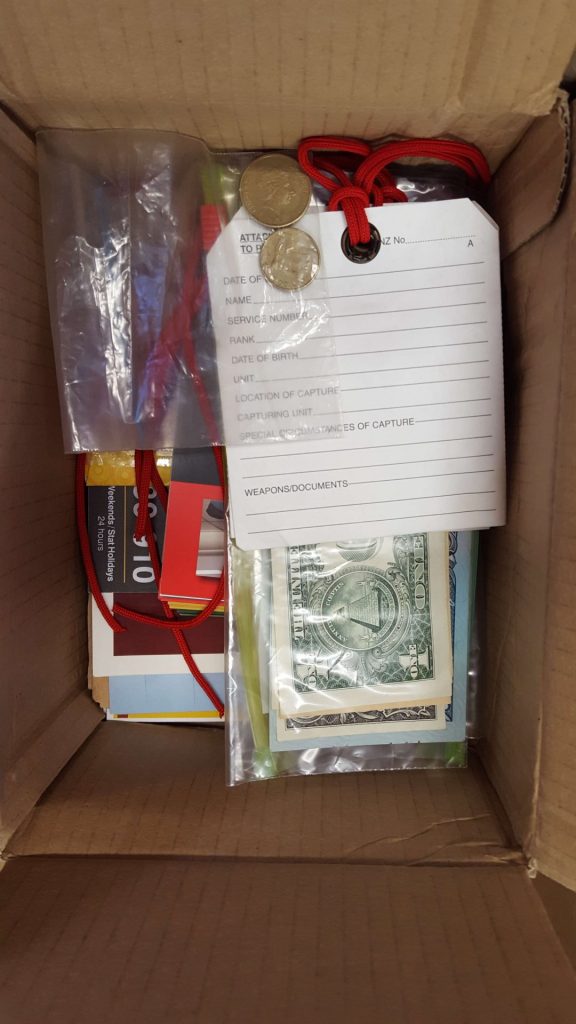

Chronology isn’t the main determinant for numbering three-dimensional objects (all the non-archival things in a collection), but we still follow a logical order designed to keep groups of items together. If a collection includes medals, those receive their numbers first. Any items of uniform are next, starting with the cap and working down. Accoutrements (such as badges and brevets) follow, then other items.

Frequently, collections will comprise three-dimensional objects and archival materials. In this situation we number all the 3D objects first (in whichever sub-groups they might divide into), followed by the archival material.

Cataloguing

Louisa:

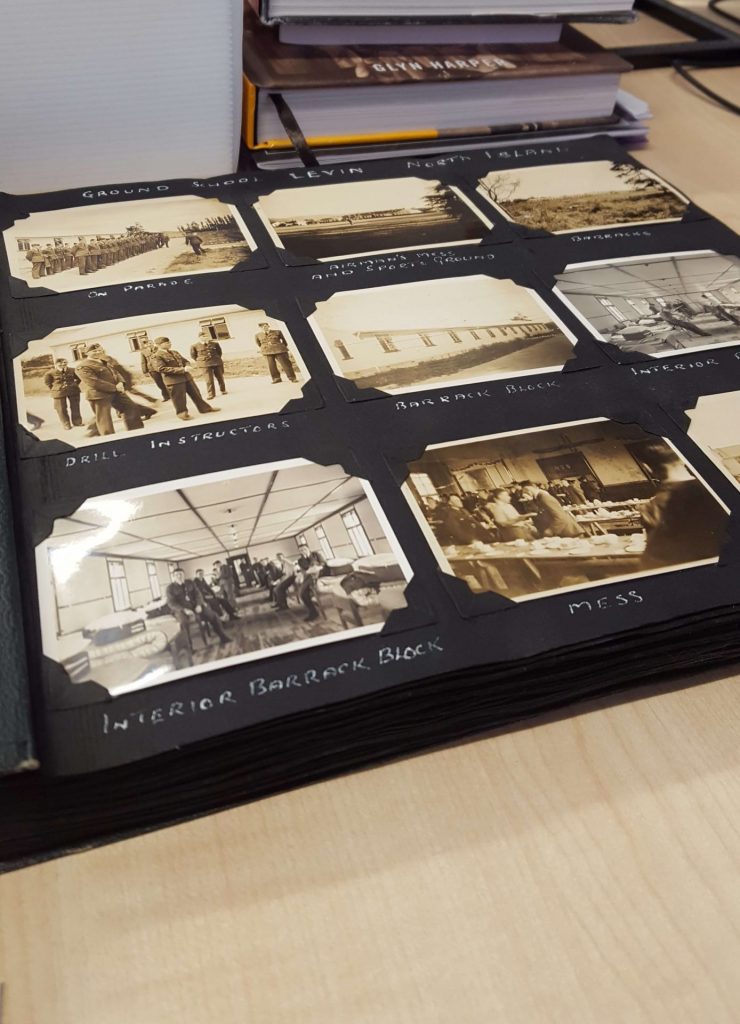

All objects in the Museum’s collection are catalogued in Vernon – whether it’s a tiny brooch or an aircraft! Archival items generally include the same basic fields as other objects, like date and location created and a description of the item. But because most archival objects are documentary in nature, there is usually a lot of extra textual information to record too, giving historical context and explaining its significance. Any captions (e.g., on the reverse of a photograph) are also recorded verbatim.

After the item is measured and condition assessed, we use an indexing function to link the record to related subject terms (people, places, events, etc.), making the object record searchable by these terms across the collection database. For log books, this means indexing all the known aircraft flown. Photographs are scanned for digitisation as part of this process; other objects are digitised on an ad hoc basis.

Murray:

Cataloguing 3D objects also follows a standard procedure and covers most of the same points. Manufacturing date, details and location are all captured if they are known. A detailed description of the object will include what it is, how it appears, and will record details such as serial numbers, in addition to its relationship to known people or events.

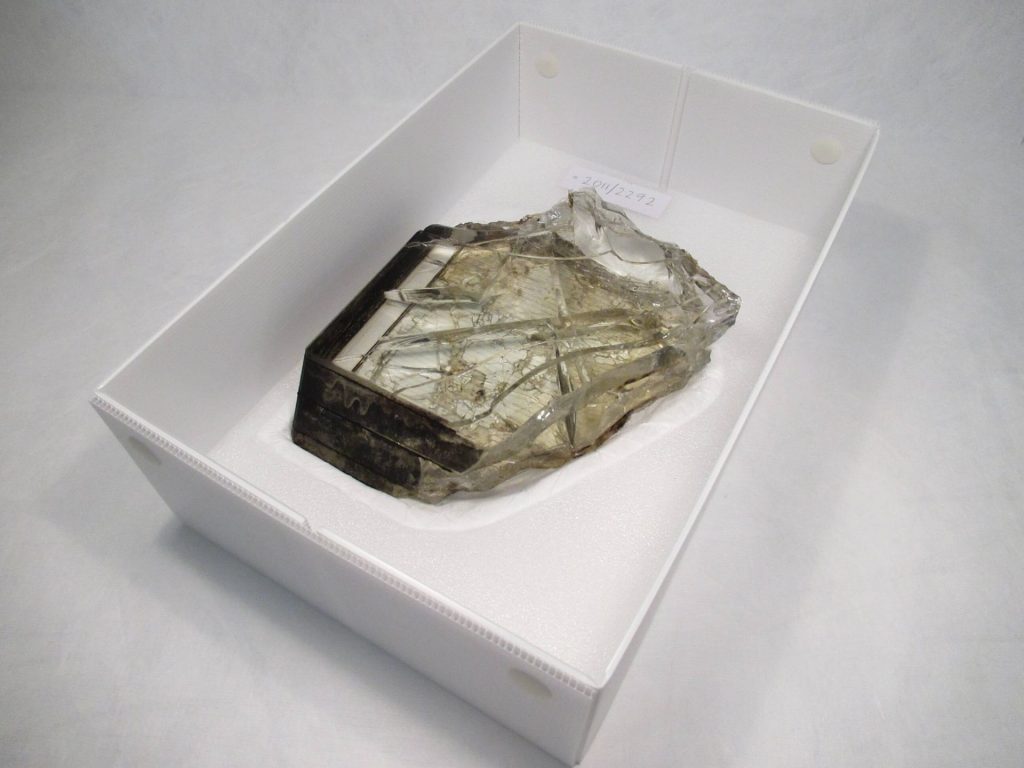

The object is measured, its component materials recorded, and an assessment is made of its condition. These details are particularly useful if an item is being considered for exhibition: we need to know the size of something if it is to go into a case or have a mount made; we need to know what it is made from in case those materials require specific environmental considerations, and we need to know whether the object is in a condition that is suitable for it to be put on display – including whether it will be adversely affected by doing so.

Subject keywords are added to aid in searching and group with like items. A photograph is taken of each item and a final shelf location recorded once it is housed.

Housing and storage

Louisa:

Literally making a ‘home’ for an object or set of objects is an important step in ensuring their long-term preservation. This involves sourcing or custom-building an enclosure that protects the object from the effects of light, vibration and contact. The materials we use to do this are chosen because they are chemically inert (non-acidic) and therefore unlikely to cause damage to the items they house. Depending on their condition, sometimes we also need to clean items (not unlike actual housekeeping)! Finally, the shelf or box location for storage is recorded on Vernon.

Murray:

Whereas archival material tends to come in standard sizes, three-dimensional objects can be anything but. Sometimes the solution is simple; in the case of many personal collections, badges, brevets, and similar items can be stored in acid-free envelopes inside a larger box.

Other objects require a bespoke approach. This usually involves carving an object-shaped recess in a plank of laminated foam, which is then lined with Tyvek to ensure a smooth surface. The object is then stored on its new base in a labelled box. For ease of management, we use standard sized boxes but sometimes these too will need to be modified to provide more height for taller objects.

The arrangement, cataloguing and storage process is an involved and time-consuming undertaking and, as you can see, requires a lot of attention to detail! But the end result is worth it and necessary for the enduring survival of these objects, which is at the core of our mahi.

Learn more about our 2021 cataloguing project

For the majority of the year 2021, our research team has been working hard on a cataloguing project. Read more about it here.