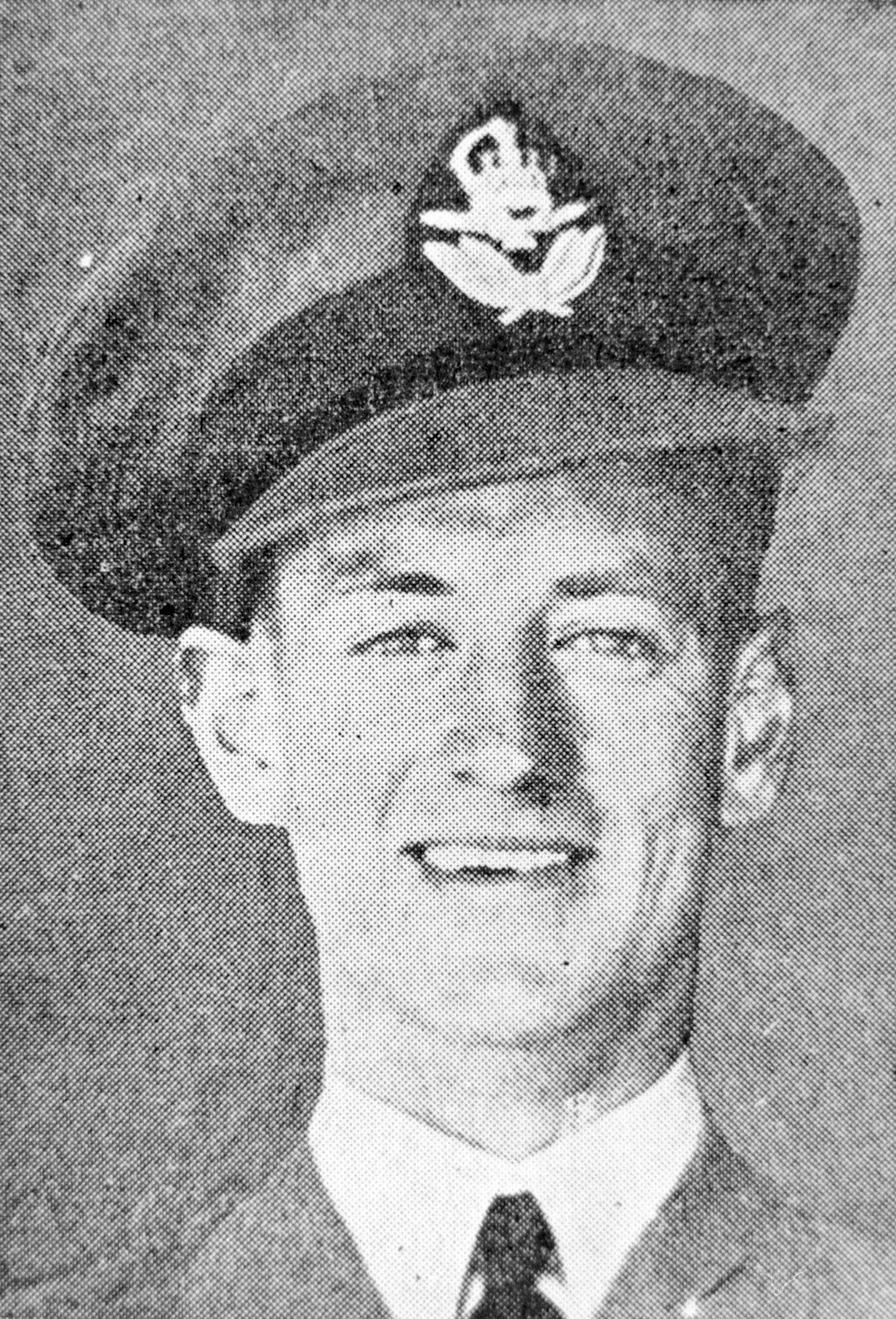

Pilot Officer Charles Edward Langdon, Royal Air Force (RAF)

Charles Langdon was one of about 130 New Zealand airmen to serve in the Battle of Britain in 1940, defending Britain from the German Air Force and possible invasion.

Charles was born in Hawera in 1918 and attended Hawera Technical High School. Prior to the war, he worked as a stock and station clerk for the local Farmers Co-op.

In June 1939, he proceeded to Britain to join the RAF as a pilot and after training as a bomber pilot he joined No. 142 Squadron flying Battle and then Wellington aircraft. He completed two bombing operations with that squadron.

It is believed that he answered the call for volunteers from the bomber units to replace the mounting losses of Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain and was posted to No. 43 Squadron flying the Hurricane in August 1940. He took part in four operational flights during the battle. He also had two forced landings but was fortunately uninjured.

New Zealanders formed the third largest group of pilots by nationality to take part, after the United Kingdom and Poland.

Later that year, Charles shot down a German fighter and was therefore credited with an aerial victory.

The Defence of Malta

In November 1940, he embarked on the carrier HMS Furious for the Gold Coast. He then ferried a Hurricane from West Africa via Egypt to the heavily besieged island of Malta, where he was posted to No. 261 Squadron on Hurricanes.

One month after arriving at Malta, Charles was one of eight heavily outnumbered Hurricanes which bravely attempted to intercept a major German and Italian raid of nearly 100 bombers on Luqa airfield on 26 February 1941. In the ensuing fight with enemy fighters, he was shot down and killed, one of three Hurricanes lost by the squadron. His body was never recovered.

Charles is commemorated on the Malta Memorial, which remembers those lost in the Mediterranean with no known grave.

Wing Commander Alan Cunningham Mitchell, Royal Air Force (RAF)

As Staff Officer (Personnel) at RAF Headquarters in Aden, Alan Mitchell was responsible for ensuring families of RAF personnel were kept safe once Italian forces began bombing in June 1940. Wives and children were often evacuated for safety, including Alan’s own wife Dorothy and baby daughter Alison, who were sent to Bombay, India. Sadly, the family were never reunited, as Alan died of peritonitis while Dorothy and Ann were abroad.

Alan was born in Balclutha in 1904, and began his military career on a Short Service Commission with the RAF in 1928. He was posted to Egypt, where he joined No. 55 Squadron RAF and received his pilot’s badge in April 1929. From 1931-1938, Alan served as a flying instructor and underwent flying boat conversion training. He became a Chief Flying Instructor, and received a Permanent Commission in the RAF.

Alan was posted to the Middle East in October 1938, where he took up his Staff Officer role in the British Colony of Aden (now in Yemen). He was hospitalised for malaria in early September 1940, from which he recovered. However, while convalescing, Alan took ill with peritonitis, an infection of the inner lining of the stomach, and died on 18 September 1940, aged 35. He was buried at Mukeiras, and later reinterred at Maala Cemetery in Aden.

Letters from Aden

In our archives here at the Museum, we have letters written by Alan during his final posting, to his wife Dorothy in Bombay. This excerpt is from a letter dated August 1940, a month before he died:

‘It [World War Two] all seems so stupid and futile but we must see it through now whatever the cost. One thing that the chance of losing the war does and that is that it gives one a sense of real values. Money & material things just don’t matter. It is the products of nature, the sea, the trees, the sun and the right to enjoy them as we wish that really counts. And you, dear sweetheart, you and your babe that is what I want. Love Alan.’

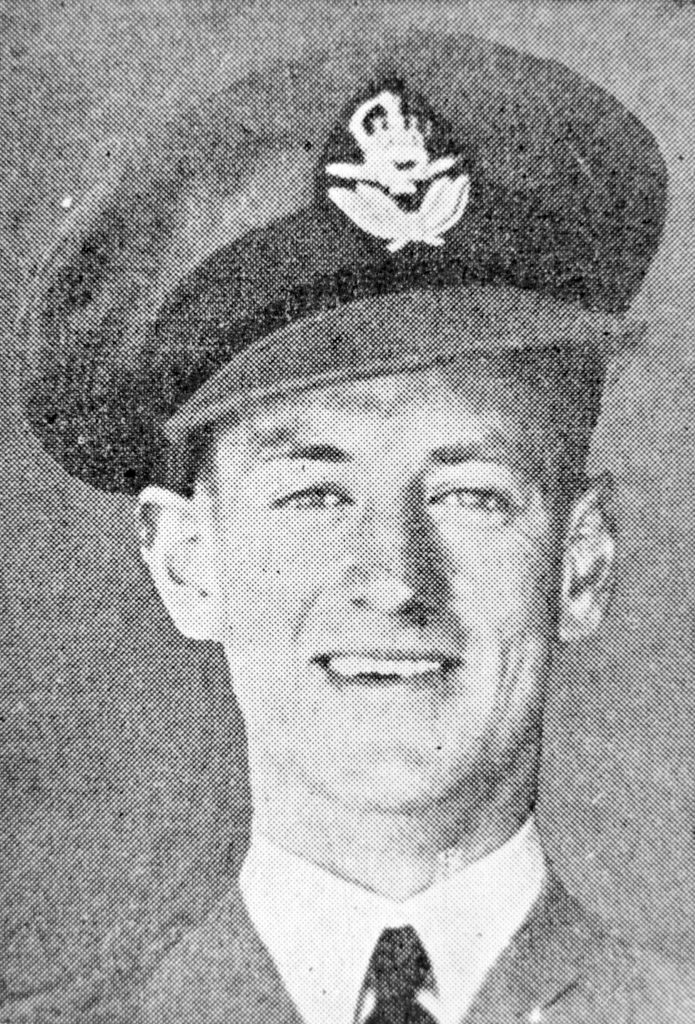

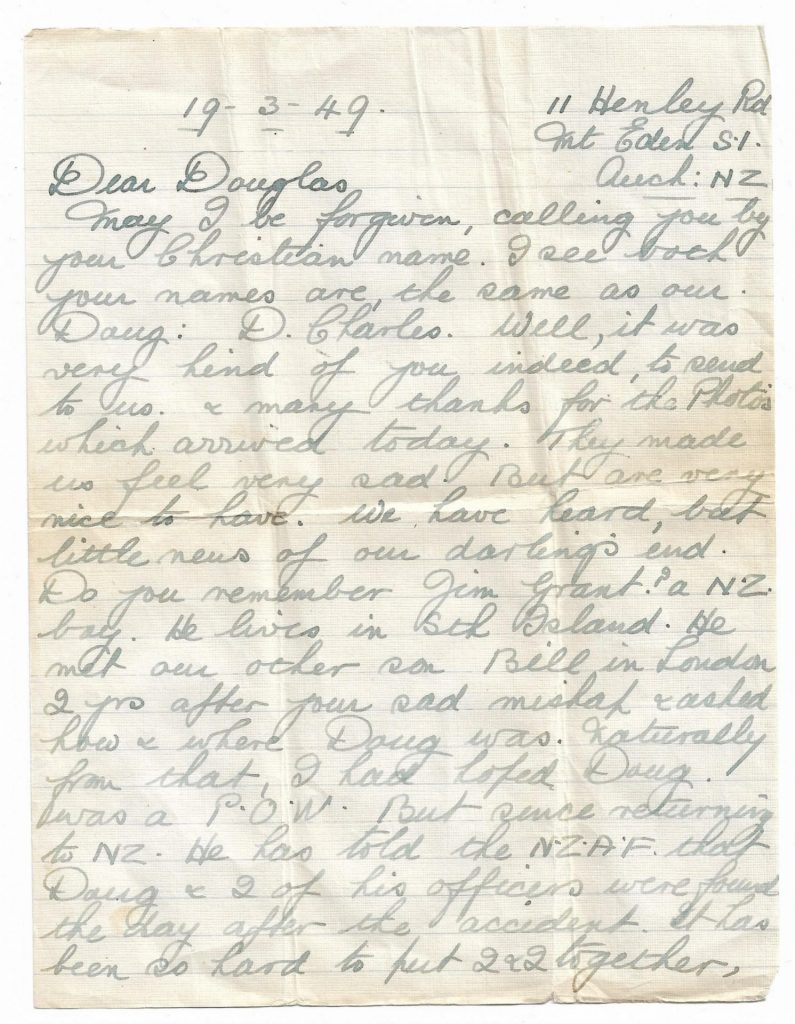

Pilot Officer Douglas Charles Henley MiD*

On 19 March 1949 a bereaved Auckland mother, Mrs Mabel Henley, wrote a letter to England. It was addressed to Sergeant Douglas Charles Box, who shared the same first and middle names as her deceased son, Douglas Charles (Doug) Henley. Both men had served on the same 75 (NZ) Squadron RAF crew, made up of three Englishmen and four New Zealanders.

Doug Henley was the pilot and captain of a Stirling bomber which took off on the night of 31 August 1943 for a raid on Berlin. Near the target area, they were badly shot up by anti-aircraft fire and German night-fighters. Doug nursed the damaged aircraft for nearly 500km, before ordering the crew to bail out as it ran out of fuel, crashing at Ahrbrück.

Four crew members were captured as prisoners of war, while three did not survive the crash. The fatalities were all New Zealanders, including the navigator and air bomber, whose parachutes failed to deploy in time, and the captain.

Writing after the death of both her sons in the war, Mabel Henley thanked Sergeant Box for sending photographs of Doug, and expressed her feelings of loss:

‘… we are two very lonely parents now. Bill was killed exactly 2 years after Doug on Aug 30th 1945. The news nearly killed me, he was to have come home the following month. We don’t get a lot of news about them. Perhaps at the time its [sic] just as well. They were two of the best & brave lads, like you all were…‘

Pilot Officer Douglas Charles (Doug) Henley mid*, RNZAF (Pilot)

Douglas (Doug) Henley of Auckland was a garage proprietor before joining the RNZAF as an airman pilot in August 1941. He trained in New Zealand before embarking for England in February 1942. Doug was posted to No. 75 (NZ) Squadron RAF on 20 August 1943 and was commissioned as an officer on the 30th, just two days before he was killed on operations, aged 23. His brother, Flying Officer William John Henry Henley DFC, died on 30 August 1945.

*Mentioned in Dispatches

Click the image above to enlarge and read the letter.

Image: Letter (page 1) from Mabel Henley to Douglas Charles Box. From the collection of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand. (2020/048)

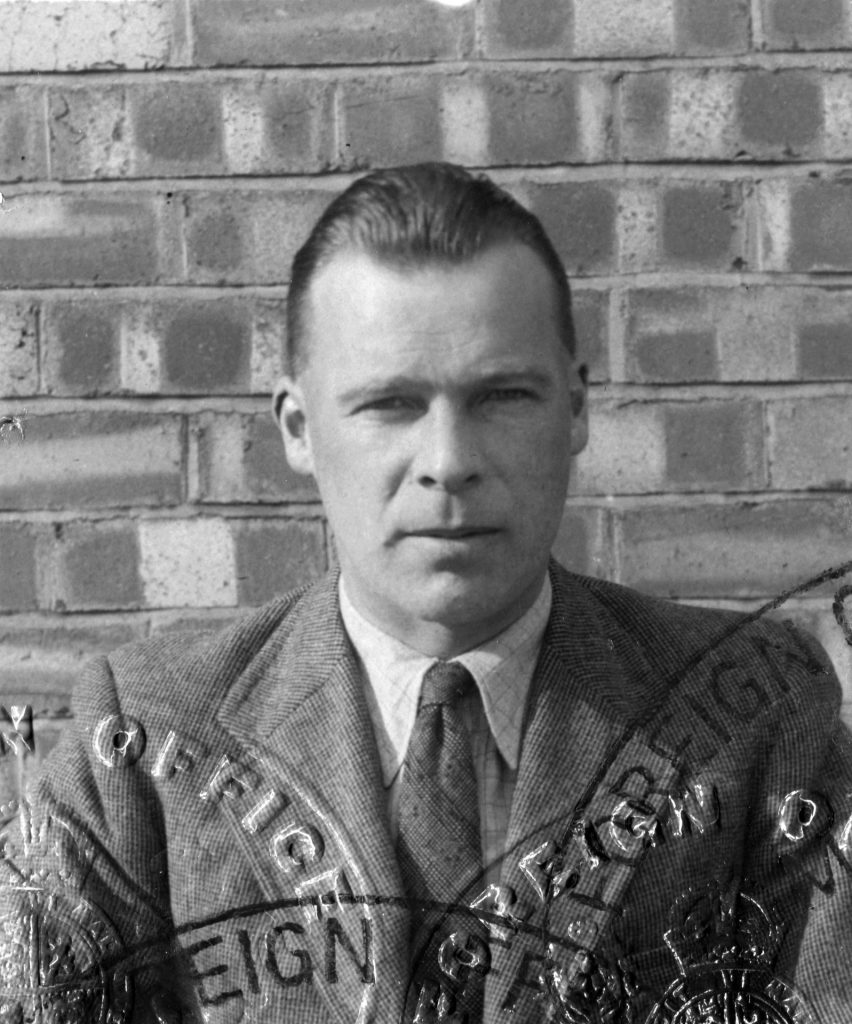

Flying Officer Ronald Wynn Russell

When we see historic photos, it’s often in isolation, telling the story of a moment in time or simply a nice picture of a thing, person or place. Seldom do people see ‘the whole picture’, that is, the rest of the photos in the collection; the ‘uninteresting’ photos; the ones that aren’t simply a pretty picture.

Taken as a whole, personal album collections often tell the whole story of a service person’s career. There’s often photos of mum and dad, siblings left at home or just the mundane aspects of training. They give us a more complete view of the individual and their service.

Ronald Wynn Russell joined the RNZAF in 1937 as a cook. He was stationed at Wigram and Hobsonville before, and in the early years of World War Two. He wanted to contribute more to the War effort and re-mustered as a pilot, learning to fly at Ashburton and graduating at Wigram in early 1943.

Ronald continued training in England and was at a Pilots’ Advanced Flying Unit on D-Day as he noted in his log book, “new front opened June 6th 1944”. Soon after, he began training for operations at an Operational Training Unit and then at a Heavy Conversion Unit.

Ronald and his crew were posted to No. 75 (NZ) Squadron RAF, and on 3 January 1945, his first flight with the Squadron was a daylight raid to Dortmund. He began operations late in the War, but still in time to make an important contribution, including daylight bombing raids to Germany, Operation Manna flights and repatriation of released Prisoners of War back to England.

Unfortunately, not all of these are depicted in his personal albums, notably Operation Manna, sadly. However, there is some rare and unusual photos and luckily, he wrote captions under most of the prints which give us valuable context and information relating to the image.

The collection consists of three photo albums, some loose prints and several loose album pages. Individually, many photos are an excellent representation of No. 75 Squadron late in the War, but collectively, they represent the RNZAF career of a young man from Geraldine in South Canterbury.

We hope you enjoy looking at the photos in this collection and the thousands of others available on the database.

Browse the Ronald Russell collection here.

Lost without trace: The disappearance of Dakota NZ3526

On 24 September 1945, barely a month after the end of World War Two, the RNZAF suffered its largest loss of life in one day when Dakota NZ3526 disappeared on its way home from the Pacific islands.

The transport aircraft from No. 40 Squadron took off from Pallikulo Field on Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) at 5.30am, bound for Whenuapai. On board were four crew and 16 passengers, all New Zealand airmen returning home from active service. At 9.06am, NZ3526 sent out a ‘standby, standby’ message, but radio contact was then lost.

Despite a large-scale search by Catalina, Dakota, Hudson and Liberator aircraft over several days, nothing more was heard or seen of NZ3526 or its crew and passengers.

The most likely explanation is that the Dakota suffered a catastrophic structural failure in turbulent air conditions, similar to weather described by an aircraft following 25 minutes behind, which was forced to climb to avoid the turbulence. No trace has ever been found of NZ3526 or the personnel on board, and they are commemorated on the Bourail Memorial in New Caledonia.

IMAGE: CASUALTIES OF DAKOTA NZ3526, FROM THE AIR FORCE MUSEUM OF NEW ZEALAND ARCHIVES

Top, l-r: LAC Oswald Ferguson Bath, Flight Mechanic (32); Flight Lieutenant Wilfred Francis Coulson, Signals Officer (38); Flying Officer Douglas Farr mid, Armament Officer (25); LAC George Firman, Armourer (22); Corporal Edmund Eaton Gossling, Fire Crew (34); LAC John Barnard Grenfell, Armourer (23); Corporal Frank Graham Haldane, Coppersmith and Metal Worker (35); Flying Officer Jack Hoffeins, Captain (24)*.

Bottom, l-r: Corporal John Douglas Jacobs, Flight Engineer (26); Pilot Officer Clifton Charles Kennedy, Wireless Operator (25); Flying Officer Alan Allister Macpherson, Intelligence Officer (28); Flying Officer Kenneth McArthur, Navigator (28); Flight Sergeant Reginald Bernard Russell, Disciplinarian (41); LAC Raymond Jonathan Taylor, Patrolman (22); LAC Douglas Stanley Thomas, Wireless Mechanic (20); Corporal Marshall Harry Wilson, Intelligence Clerk (21).

The Air Force Museum does not currently hold photographs of the following casualties: LAC Harry Faine, Driver (25); LAC Frederick John Kearney, Aircrafthand (22); LAC David John Reid, MT Mechanic (26); LAC Ralph Gordon Savage, Carpenter (36).

We will remember them.

*Pilot Jack Hoffeins had a lucky doll, which he failed to take on this fateful flight. This doll is now in the collection here at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand. To read more about its story, see our ‘Lucky Charms and Superstition’ blog, here.

Flight Lieutenant Edward (Ned) Hitchcock

‘P.S. Unharmed, undamaged – and full of beans. P.P.S. Probably returning to unit shortly. P.P.P.S. Items lost – aid appreciated: one watch, First aid kit, pyjamas, Hussif.’

So wrote Ned Hitchcock home to his family, five days after his landing at Omaha Beach. Ned was one of over 10,000 New Zealanders on active duty with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy during the D-Day landings at Normandy, France, on 6 June 1944. But serving as an electrical engineer officer in the RAF, he never expected to be part of the Allied invasion:

‘I remember thinking …. just ahead of them they’ve got this fantastic operation in which they will be launched on the French coast against enemy forces. And I dismissed that from my mind, it wasn’t in my territory at all.’

Ned was one of 28 people recruited by the RNZAF to work with the RAF on coastal radar in Britain. Armed with an Honours degree in electrical engineering from Canterbury University College, he arrived in Liverpool with the other New Zealand recruits, many of whom were amateur radio operators.

After completing his training and a period of instructing, Ned was eventually given a commission and posted to a Bomber Command base at Swanton Morley in Norfolk, as officer in charge of the electrical section. Finally, with his transfer to 60 Group, he began work on the administration of all coastal radar stations in the United Kingdom.

The Landing

To his surprise, Ned’s squadron leader, Norman Best, asked if he wanted to go over with the invasion, to which he recalled saying, ‘Oh that sounds good.’ As the two RAF radar units assigned to the invasion were to be landed at the forefront, it was decided two experts join the operation. Ned and Norman were seconded to the Ground Control Intercept (GCI) radar unit allotted to the Americans, scheduled to land on Omaha Beach.

Ned’s landing craft stood offshore on D-Day, watching the fires burn on shore while the navy fired shots overhead. This followed a failed first attempt to land, stalled by the fact the beach had not yet been captured. It was during this first approach that Ned first witnessed what he later called ‘this realism of war’:

‘There was an explosion and a man’s figure went up in the air. You know, you read the term ‘blown up’- this is right in front of our eyes.’

The next day, twelve men from Ned’s party were killed and 40 more wounded during their landing. Writing home from ‘Somewhere-in-France. 12/6/44’, Ned offered his family an understated account of his own experience:

‘Later that day we went ashore, not an all round pleasant experience. Jerry was landing the occasional shell on the beach, and some of our vehicles struck a deep patch of water, and stalled. My own vehicle was one of the unfortunates, and although we managed a line to a winch vehicle, the sand was too soft and they were unable to move us.

‘So, alas and alack, deserting my kitbag, but in full webbing and respirator, I had to swim ashore. My watch has stopped firmly at that hour, and the Service Camera with which I had been taking records of the epoch making scenes, was also somewhat discouraged by salt water. Such was my first sea-bathe of the season!

‘We had considerable trouble on the beach, and suffered quite a few casualties until we eventually got what was left of our vehicles out of the water and off the beach.’

On return to England, Ned was sent on other assignments to work on radar, including making a second landing on the Normandy beaches in September, and spending some months serving in war-torn Belgium.

Post-war

Ned Hitchcock returned to Aotearoa after the war, where he worked for 20 years as an engineer for New Zealand Railways, then as technical director for the Standards Association. He married English nurse Joan Bull in 1950, and later moved with his family to Malaya while he worked on the Colombo Plan (Asian economic and social development programme). Ned completed his PhD in technological law in 1980, continuing to work as a consulting engineer until his retirement. He passed away in 2006.

Image credit: From the Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

Group Captain Desmond (Des) Scott DSO OBE DFC

In January 1944, at RAF Hawkinge, Wing Commander Des Scott successfully pulled an unconscious and badly injured pilot from a burning Spitfire, despite several explosions and sustaining light burns in the process. Although the pilot died of his injuries, Des received the OBE for his ‘great gallantry and complete disregard for his own safety’. Reflecting on such tragedies and his own long combat service, he later wrote,

‘The passing years have in no way erased the magnitude of each brief encounter, for death is a very personal thing for those who flew face to face with it.’

Wartime service

Born in Ashburton in 1918, Des Scott joined the RNZAF in March 1940 and trained as a pilot, embarking for the UK in August 1940 and becoming a highly successful fighter pilot in the RAF during 1941-2. By the autumn of 1942, he had reached the rank of Squadron Leader and spent some time as a Staff Officer at Fighter Command. Des returned to operational flying on Hawker Typhoons flying ground attack missions and took command of No. 486 (NZ) Squadron in April 1943. In September 1943 he commanded the Tangmere Typhoon Wing and by March 1944 commanded 123 Wing, taking them to France and across Occupied Europe until VE Day in May 1945. He also became the youngest Group Captain in the RNZAF, when he was promoted to the rank in July 1944.

Des became one of the most highly decorated RNZAF fighter aces of the war, destroying 6½ aircraft with 4 probables and five also damaged. Besides his British postnominals, he also received the Croix de guerre avec palme (Belgium and France) and Commander of the Order of Orange Nassau. After the war, Des recorded his wartime experiences vividly in the books Typhoon Pilot and One More Hour published in 1982 and 1989 respectively. He died in Christchurch in 1997.

Image credit: PR8832b ©RNZAF Official

Flying Officer Cyril Ironside

“A bad dream has finally ended and now I can start to live again and carry on wherever we left off such a long time ago.”

These were the words written by Flying Officer Cyril Ironside to his wife Rena in September 1945, after his liberation from a Japanese prisoner of war camp. For three and a half years, he had endured a brutal captivity and was fortunate to survive.

Cyril was born in Dunedin in 1906 and attended Otago Boys’ High School. At the outbreak of war in 1939, he was the representative of academic publisher, the International University Society in New Zealand. In 1940 he was transferred to Sydney and decided to sign up for the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve as an officer. He was then posted to Singapore prior to the outbreak of war with Japan.

The beginning of the Japanese attacks on 8 December 1941 saw him at the airfield at Alor Star, in Northern Malaya where most of his belongings were destroyed by bombing. He then assisted in the hasty evacuation of RAF airfields in advance of the rapid Japanese advance down the Malayan peninsula.

By Christmas 1941 he was in command of the Motor Transport Pool at Bukit Timah, on Singapore island. On 11 February 1942 he evacuated on the liner SS Empire Star with his men and vehicles. The ship was one of the last to leave the doomed city of Singapore and was harried by Japanese air attacks all the way to Batavia on the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Cyril wrote sadly of his departure from Singapore:

“We were no heroes and as we returned the waved farewells on the nearby island gun-emplacements one could not help feeling that we were leaving them in their hour of need – should we have disobeyed orders this once and stayed with them?”

FAR EAST PRISONER OF WAR

The ship arrived at Batavia on 15 February 1942, the day Singapore fell. He spent the next two weeks , preparing for its defence, before it too fell to the Japanese. On 8 March 1942, he and 50 other RAF personnel surrendered and were taken to a makeshift camp to join many others at Tasik Malaja airfield. What many of the prisoners did not realise was that the Japanese had no interest in the Geneva Convention or any rules of war regarding prisoners. To be captured alive by the enemy was considered a dishonour and so the prisoners would be treated accordingly, without rights or welfare provided.

Cyril clearly kept a record (now lost) and published his experiences in an article in February 1946, just a few months after his return to New Zealand. It condemned the now-defeated Japanese and outlined his experiences. During his time as a prisoner, he endured terrible treatment and witnessed a great deal of suffering. Shortly after his capture, two officers and non-commissioned officers were shot for trying to escape. He was then moved to Borneo, where many prisoners died of disease and then on to Surabaya in eastern Java. Here, dysentery killed many more as the prisoners demolished old buildings to build new ones for the Japanese. Cyril wrote of the indifference of the Japanese Commandant to the suffering of the prisoners when approached:

“The prisoners were pigs and must live like pigs”.

After a period at a ‘rest-camp’ to prepare the starving men for more work, Cyril ended up at Haruku Camp on a coral island of the same name west of Papua New Guinea. This notorious camp had several Japanese and Korean guards who terrorised the prisoners with beatings. Disease also tore through the camp and the hard coral surface tore through the shoeless feet of the prisoners.

At the end of 1944, after periods at several other camps, Cyril was commanded a group of prisoners bound by ship for Surabaya on Java once more. Told by the Japanese that the ship would not stop for any prisoner who fell overboard, one critically sick man did. He was recovered and beaten. Cyril was punished with the sick man for ‘not obeying my orders’. He later wrote:

“I was called onto the bridge, and when I arrived the Japs were discussing trailing me behind the ship on a piece of rope. I was given a good thrashing instead, the results of which I am still suffering. I was beaten about the head by a rope….and I am pretty deaf in one ear”.

January 1945 saw Cyril back in Singapore, working on the docks, where he remained until the Japanese capitulation there on 12 September 1945 and his own liberation. His wife Rena was informed he was safe and suffering from nothing worse than malnutrition.

Like many prisoners of the Japanese however, Cyril had endured an horrendous experience both physically and mentally and some of the worst cruelty known in the history of war. His was a heroism of endurance. Despite his optimism for the future, Cyril’s life was to be shortened by his captivity. Settling in Gore, he suffered from recurrences of his head injuries. In 1961, at the age of 55, he died following a brain haemorrhage, almost certainly the result of the beatings he had received to his head.

Ka maumahara tonu tātou ki a rātou.

We will remember them.

Image from the collection of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

SECOND OFFICER JANE WINSTONE

Whanganui schoolgirl Jane Winstone began flying at age 16. She flew solo at 17, becoming New Zealand’s youngest woman pilot at that time, and the first female member of the Wanganui Aero Club to fly solo.

Following the outbreak of World War Two, Jane travelled to England, and, after passing her tests, joined the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). This civilian organisation helped the war effort by ferrying military aircraft from factories or maintenance units to Royal Air Force (RAF) stations within the United Kingdom, and transporting mail, secret documents and service personnel on urgent duties.

Jane was serving with No. 12 Ferry Pool ATA when, on 10 February 1944, she was tasked with ferrying a Spitfire from Vickers Aircraft at Cosford to 39 Maintenance Unit RAF at Colerne, Wiltshire. Upon takeoff, the engine failed and while attempting a forced landing, the fighter spun and crashed into nearby Tong Lake, killing the 31-year-old pilot. She is buried at Maidenhead (All Saints) Cemetery in Berkshire, United Kingdom, in a section set aside for ATA casualties.

The Jane Winstone Retirement Village in Whanganui is named in Jane’s honour.

Female Air Transport Auxiliary pilots from New Zealand, serving 1939-1945:

Jane Winstone was one of five New Zealanders among the 90 women who served in the ATA during World War Two, and one of 16 ATA women killed during the conflict. The four other New Zealand women survived the war:

1st Officer Trevor Hunter (m. Colway)

1st Officer Betty Elice Black (m. Beaumont)

3rd Officer June Constance Howden (m. Gummer)

Cadet Edith Elizabeth ‘Marie’ Furkert (née Power-Collins)

Flight Lieutenant William Allison

Just 11 years older than David, William was born in Christchurch and gained his pilot’s license flying with the Canterbury Aero Club. After qualifying, he worked as a Union Airways pilot and was commissioned as an officer in the RNZAF on 15 October 1939.

William served as a flying instructor with No. 1 Flying Training School and No. 2 Squadron (attached to the School of General Reconnaissance), before being posted to the Pacific on 21 March 1943, flying Hudsons with Nos. 4 Squadron, 9 Squadron and 3 Squadron.

On 24 July 1943, William was the captain of a Hudson flying a patrol between New Georgia and Bougainville when they were attacked by eight Japanese fighters. They battled for over 60 kilometres until, on fire and with three wounded crew, the aircraft ditched two miles west of Mbava (Baga) Island, New Georgia. The survivors, including William, abandoned the aircraft, but they were then machine-gunned in the water by the enemy fighters, leaving only one survivor.

William is commemorated, alongside his four fellow crewmen and one Army passenger, on the Bourail Memorial in New Caledonia.

Flight Sergeant David MacLean

David ‘Derek’ MacLean grew up in rural Whanganui and studied at Victoria University College before enlisting with the RNZAF as an airman pilot on 1 March 1941. In June, he embarked for Canada, where he continued training and gained his Pilot’s Badge on 25 September 1941. After further training in England, he began flying Spitfires and joined No. 19 Squadron RAF before embarking for the Mediterranean.

Derek was serving at Luqa, Malta, with 126 Squadron when, on 11 October 1942, he was tasked with intercepting an incoming raid of over 50 aircraft. He took off in his Spitfire with eight others, but was shot down into the sea about 35 miles north of Comino Island. Derek is commemorated on the Malta Memorial.

PILOT OFFICER ERNEST (TONY) COX

Tony Cox was born and raised in Christchurch, and worked as a clerk at a local accounting firm prior to World War Two. He enlisted in the RNZAF in May 1941 and after completing pilot training at Taieri and Wigram, was posted to No. 488 Squadron RNZAF in September. Tony embarked with the Squadron for Singapore later that month, arriving on 10 October 1941.

Just before midday on 18 January 1942, 488 Squadron aircraft scrambled to intercept a Japanese raid. Tony took off with his unit from Kallang Airfield, but on the ascent through 16,000 feet, the formation was attacked from above. Tony’s aircraft was last seen around 12.30pm diving into a cloud over the Singapore Strait.

Tony was 22 when he died. He is commemorated on the Singapore Memorial at Kranji War Cemetery, his name etched alongside the names of over 70 New Zealand airmen who lost their lives while serving in the region and have no known grave.

“And Some Have Greatness Thrust Upon Them”: a poem for 488 Squadron RNZAF

Written archives help preserve the thoughts, experiences and memory of young people like Tony who lost their lives on active service.

In our archives, we have a poem written by Pilot Officers Tony Cox and Harry Pettit. This poem was performed at the Christmas Day Smoke Concert held at Kallang in 1941, less than a month before Tony was killed on operations. The final stanza is both poignant and resolute:

And now we close this ditty with the heartfelt prayer,

That you may all have a prosperous New Year,

The ruddy little Japanese may make things mighty warm

But you just watch them scatter, when 488 strikes form.

Excerpt from typed poem “And Some Have Greatness Thrust Upon Them” by Pilot Officer Tony Cox and Pilot Officer Harry Pettit, RAF Kallang, 1941 (2007/529.9).