Take as your inspiration one of the most famous events of World War Two, when the Royal Air Force (RAF) successfully defended Britain against a sustained aerial attack by the German Luftwaffe that was intended to break the country and prepare the way for invasion. Combine this with decades of design and production know-how, then throw in 26,000 miles of Egyptian cotton thread and maybe you can’t help but create a little bit of magic. Known prosaically on our collection database as ‘Object 2009/468’, the Battle of Britain Lace Panel is a special thing indeed.

Background

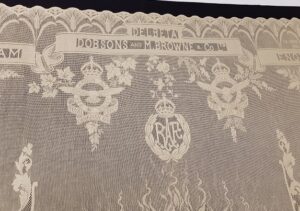

Between 1942 and 1946, approximately 38 large commemorative panels were produced by lace manufacturer Dobsons and M. Browne and Co. Limited, of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. Like many commercial operations at the time, the textile producer was contributing to the war effort by making mosquito nets and camouflage rather than the curtains and other decorative items for which it was more well known.

Because decorative camouflage and lace mosquito nets would have been of limited use in a combat zone (unless the mosquitoes were very large, in which case you might have had problems that fabric couldn’t solve), the lace design skills usually employed at Dobsons and Browne weren’t in great demand over this period. They would, however, be essential once normal business resumed and it was important for the company to retain them. Managing Director M.J. Were’s decision to produce the highly decorative Battle of Britain panels enabled his team to continue practicing their skills while they created a fitting tribute to the people and events of the Battle of Britain.

The company intended to present the completed panels to individuals, military units, towns, Commonwealth nations and other entities that had contributed to the Battle of Britain or were directly affected by it. This select group included King George VI, Sir Winston Churchill, the cities of Nottingham and London, Westminster Abbey, various RAF units, some members of the Dobsons and Browne staff and the countries of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa. Whether all the presentations were made as planned is unknown, but there are believed to be 31 panels still in existence, mostly held by museums and private collectors.

The Design

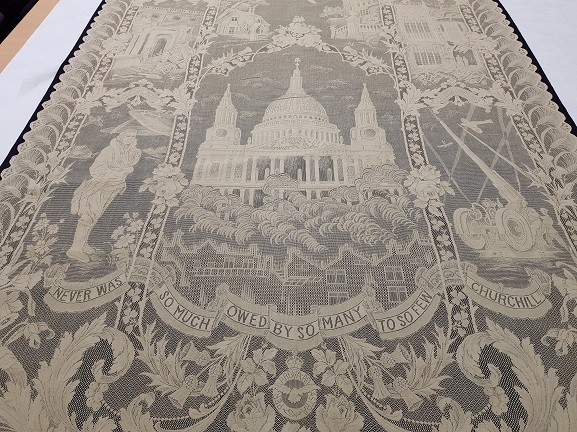

What may not be immediately obvious about the panels from a photograph is their size. Each one is a whopping 15 feet (4.5m) long and five feet six inches (1.6m) wide.

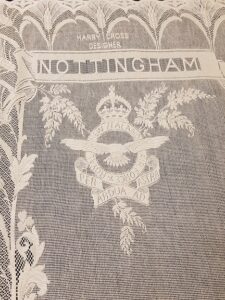

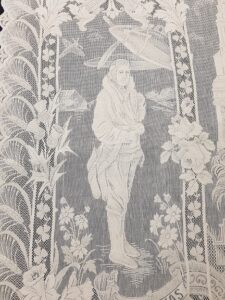

The scenes and content were designed by Harry Cross who, at 73 years of age at the time, had been designing lace for almost 60 years. The images tell the story of the defence of Britain and the Luftwaffe attacks on London and South East England during the Summer and Autumn of 1940. In doing so, the panels continue a tradition of narrative textiles embodied by objects such as the Bayeux Tapestry. The design is full of symbolic references.

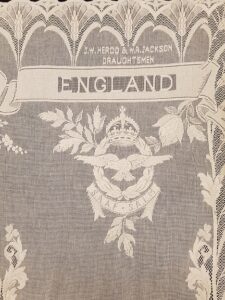

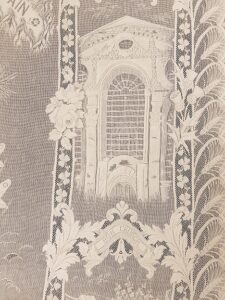

The content is divided into three columns with horizontal ‘bars’ at the top and bottom. The company’s own details feature across the top, and the prominent positioning of their curtain brand ‘Delbeta’, suggests that the panels served a promotional purpose as well as a commemorative one. Harry Cross is name-checked at the upper left, while the names of draftsmen J.W. Herod and W.R. Jackson appear at the right.

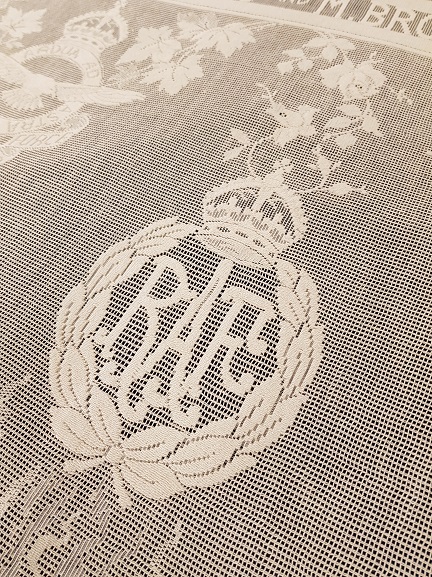

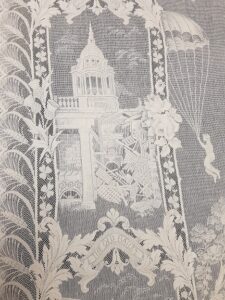

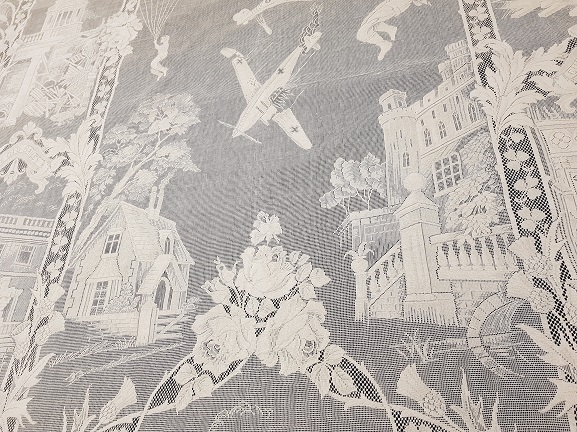

The badge of the Royal Air Force and those of the four contributing Allied Air Forces appear immediately below, with plants representative of each country. The Royal New Zealand Air Force badge is at the left, surrounded by silver ferns.

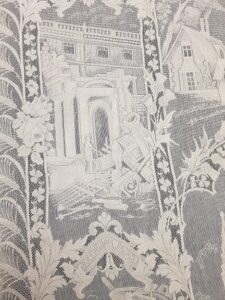

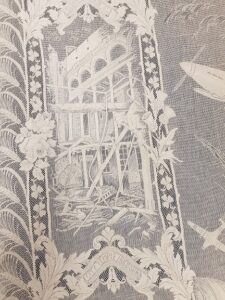

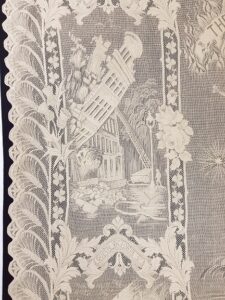

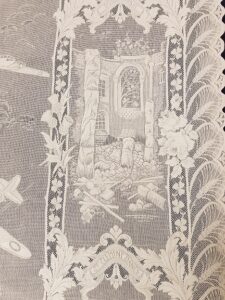

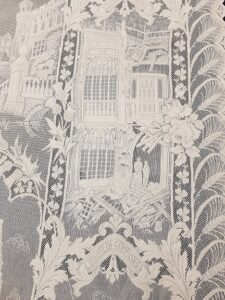

The columns on the left and right sides depict many well-known London buildings that were damaged during the aerial bombing campaigns. They include a collapsed façade with fire fighters in attendance in Queen Victoria Street; City Temple, Holborn, in ruins; The Old Bailey; Buckingham Palace, with damage to the gates; Bow Church; the RAF church of Saint Clement Danes; the Guildhall and the House of Commons. A pilot at the bottom left symbolises the young men of Fighter Command and an anti-aircraft gun and searchlight opposite depict the contribution of the ground defences of London.

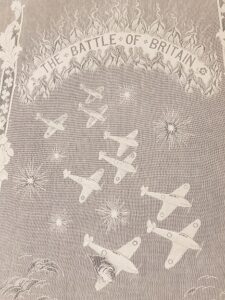

The central column is the most prominent. Beginning with a flaming banner that declares ‘The Battle of Britain’, it portrays an aerial battle with RAF Spitfires, Hurricanes and a Defiant fighter engaged with German Dornier bombers, Stuka dive bombers and Messerschmitt fighters. Two parachuting pilots are also shown and, beneath them, a cottage and a large country house symbolise how the events affected people irrespective of wealth (although you can imagine that quaint-looking cottage receiving a breathless write-up and a high asking price were it to appear in a real estate listing today). Finally, Saint Paul’s Cathedral stands behind a silhouette of burning buildings. The cathedral became a symbol of defiance as it remained largely untouched by the bombing – and wholesale destruction – of the city around it.

Equally potent and laid out in a banner across the lower portion on the panel are Sir Winston Churchill’s well-known words regarding the Battle: “Never was so much owed by so many to so few”.

Floral detail appears across the object. Shamrocks, thistles, daffodils and Tudor roses – the respective emblems of Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England – are visible throughout, along with plumes of oak leaves. The whole piece is surrounded by a border that shows ripening corn, referencing the time of year the events took place.

How it was made

Harry Cross’s design process took two years, during which he worked from photographs, postcards and other illustrations. Draftsmen intricately plotted his design onto squared paper and calculated the thickness of threads required – a process that took a further fifteen months. J.W. Herod undertook the initial drafting work, with W. R. Jackson later taking over after Herod’s death.

The panel was woven using a Jacquard mechanism, one of many inventions that had transformed the textile industry over the course of the Industrial Revolution. Invented in 1804, the Jacquard mechanism was a piece of equipment that enabled complex patterns to be machine-woven when it was attached to a suitable loom. The mechanism relied on a series of punch cards that rotated around a square drum. The placement of holes on each card determined the operation of a series of rods connected to hooks that ultimately raised or lowered individual threads on the loom. With punch cards controlling how a machine functions (and the cards written in a binary language of ‘punched’ or ‘not punched’), the Jacquard mechanism is regularly cited as a forerunner to modern computing.

40,000 cards were required for the Battle of Britain Jacquard, and it took Alf Webster six months just to punch the holes in them. Once the cards were stitched together the strip weighed more than a ton. Each panel took around a week to produce once manufacture was underway.

Our panel

A panel was given to each of the Dominion Air Forces, and New Zealand’s was presented to the former National Museum by Mr F. C. Renouf of Hataitai on 13 April 1949. The panel was on loan to the Air Force Museum for more than ten years before it was returned to Te Papa in 2000 for conservation due to the prolonged period it had been exposed to light whilst on display. This panel can be viewed on Te Papa’s online catalogue.

The Air Force Museum acquired its own panel in 2008. It is believed to be one of several originally given to directors of Dobsons and M. Browne and Co. Limited in 1947. It was later given to a Mr Leonard Anderson, a chemist at Boots, by his secretary as a gift for Anderson’s daughter in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). On arrival in Africa it was carefully packed away and was only displayed publicly on one occasion, where it was hung from a balcony at a local school to mark a visit by Battle of Britain hero Douglas Bader. Although it was already backed with silk, a sturdier black fabric backing was tacked to the panel at this time, enabling it to be hung. This backing remains in place. The panel returned to the United Kingdom in 2007 and was subsequently purchased from the family.

Because of its size and sensitivity to light, the panel is not suitable to be on permanent display. It is stored loosely rolled and its delicate construction means that we like to handle it as little as possible. But we don’t want to keep it hidden from view, and we don’t have to! Virtual platforms such as this blog offer a perfect opportunity for us to show off the panel and other items that might not be easy to exhibit. We are therefore able to make objects available for view while addressing conservation concerns.