New Zealanders have been deployed around the world with the Air Force for more than 100 years, and many of the sights that they’ve seen along the way are documented in our archives. From mosaics to temples, and a touch of graverobbing, let me take you on a little tour of some historic and archaeological sites that feature in our collection.

Estimated to have been built in the 12th century, the Polonnaruwa Vatadage in Sri Lanka is one of the more easily identifiable sites represented in our collection. A vatadage was built for protection around a stupa, a small circular structure which housed a relic — in the case of Polonnaruwa, this was believed to be a tooth of the Buddha. While having some influence from Indian architecture, the vatadage is largely accepted to be more or less unique to the architecture of ancient Sri Lanka.

Dating just after the Polonnaruwa Vatadage is the Great Buddha, built in the middle of the 13th century in Kamakura, Japan. This statue is a hollow bronze casting and was previously gilded. It measures over 10 metres tall, dwarfing the servicemen and children gathered beneath. Several natural disasters which destroyed the temple built around the statue means it has been exposed to the elements for over 500 years.

From further back in history, we now move to Cyprus, and the Ancient Greek city-state of Kourion, or Curium. First, we have a wonderfully preserved mosaic of a woman with the word κτισις (ktisis) around her. After an estimated 8.5 magnitude earthquake struck Crete in 365CE, there was widespread destruction in the Mediterranean, including Cyprus. An otherwise unidentified man built and gifted a house to the people of Kourion, with it eventually becoming a public space and bearing his name to be known as the House of Eustolios. Ktisis, when presented like this, is the personification of the act of giving a generous donation or foundation, and this imagery being present in such a gift to the people of Kourion indicates what it meant to receive it.

This mosaic, while badly damaged, is still recognisable and identifiable as one belonging to another site in Kourion known as the House of Achilles. This is the most important mosaic in a set within the complex that depicts Achilles (centre), as this shows Odysseus (right) revealing his true identity, after he had been sent in disguise as a woman to the court of Lycomedes of Skyros to keep him from fighting in the Trojan War. To the left of Achilles is Deidamia, his wife and a daughter of Lycomedes — the lettering besides these two figures identifies them as such.

Last but not least from Kourion, we have one of several photos of Corinthian columns. This style of architecture is characterised by the most decorative of capitals (top section) usually featuring acanthus leaves, as with these. The Corinthian column was the successor to the earlier, less flamboyant Doric and Ionic orders, with the servicemen in this photo giving scale to how tall these are, and how truly impressive the building must have been originally.

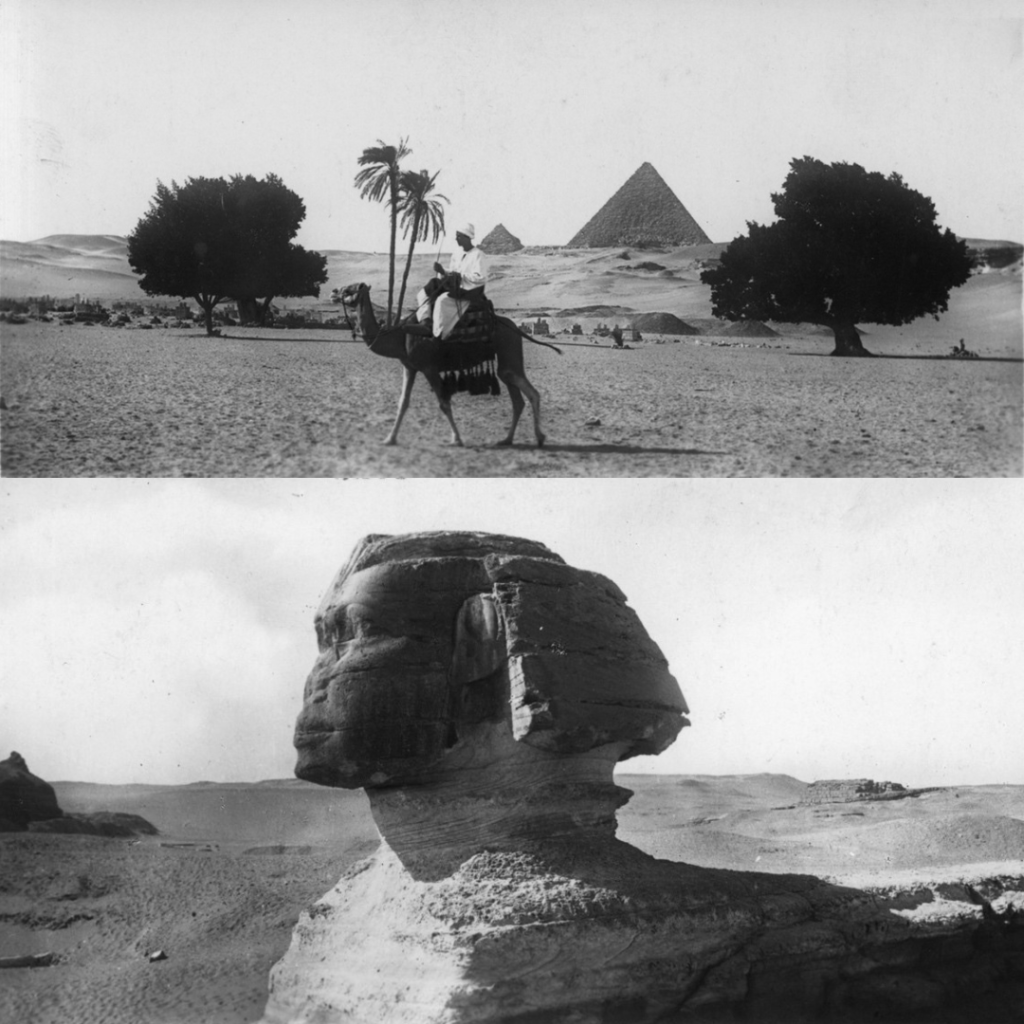

Delving a little further back into history, we have a perfect example of things not to try at home — in my opinion, anyway. This group of seven servicemen is seen outside the Pyramid of Khufu, one of the Great Pyramids of Giza, with one sitting on a statue outside one of the entrances. While the golden age of Egyptology had run its course by the time this photo was taken around 1944, the allure of the pyramids, and Egypt itself, inevitably remained. At this time, it had been just over 20 years since Howard Carter excavated arguably the most famous tomb — that of Tutankhamun — throwing the world into a renewed excitement over Egyptian archaeology.

Before even this happened, however, Kiwis were stationed in Egypt with the Royal Air Force, including during World War One (1914–1918). In amongst the letters and logbooks of the archive here at the Museum is a map provided for servicemen stationed in, or near, Cairo.

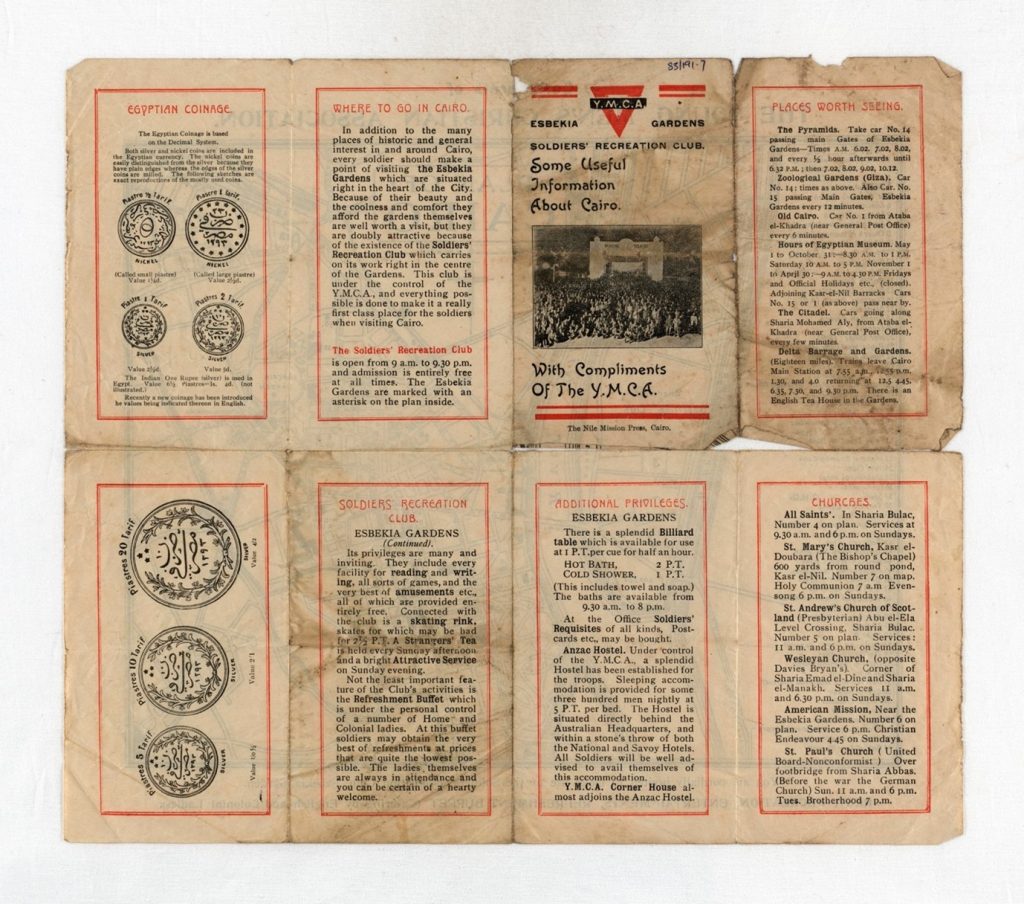

The Esbekia Gardens YMCA Soldiers’ Recreation Club published a pamphlet entitled “Some Useful Information About Cairo” which includes information regarding Egyptian coinage and its conversion to British currency, as well as “privileges” or amenities provided in the YMCA building, and a list of both local churches and places to see. The reverse of the pamphlet folds out into a map of Cairo with streets named, rail and tramways noted, and a list of buildings and sites to take note of. For Kiwis in Egypt for the first time, this map would have proved to be worth its weight gold (probably more) and this is evident in the wear and tear to the map.

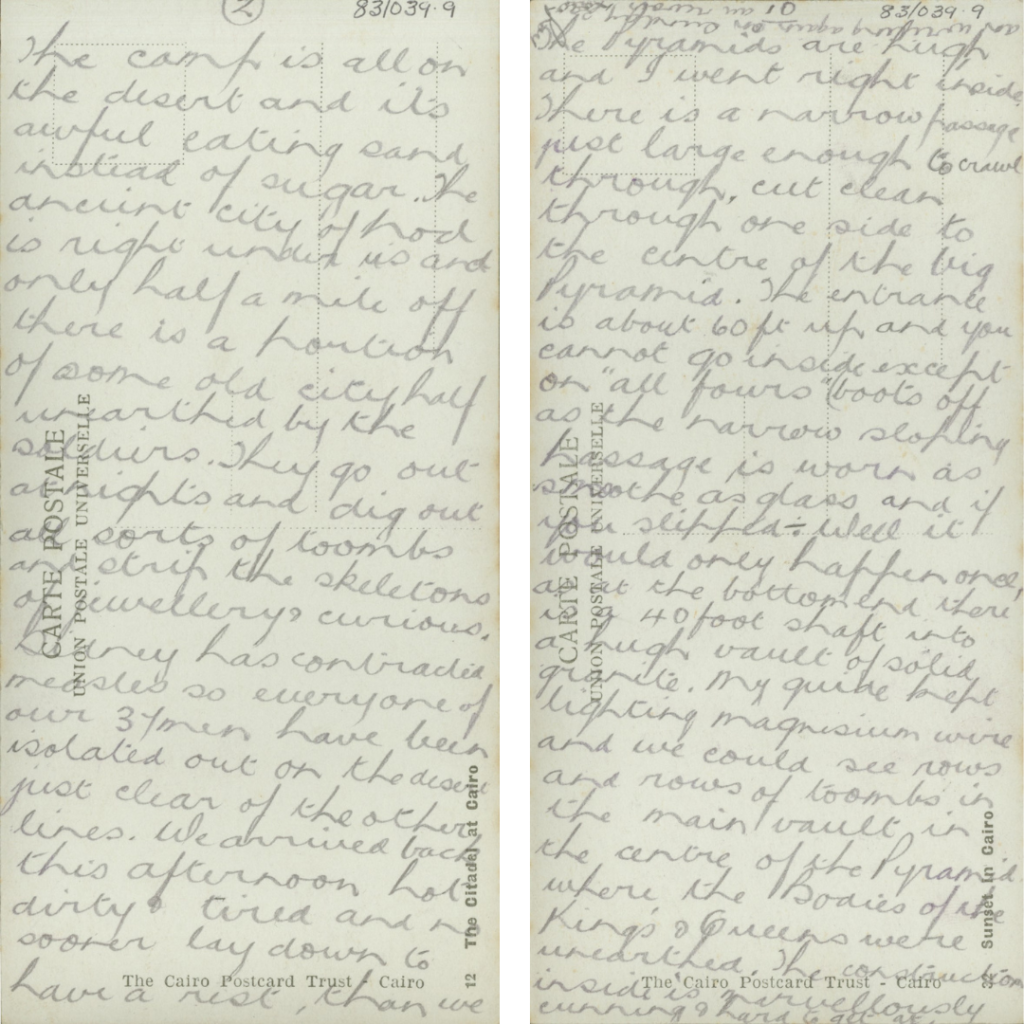

However, while some people were going to the YMCA for a nice game of billiards on the “splendid” table they had there, others were dipping off to the Pyramids and other places to either buy or steal items inside. During the First World War of 1914 to 1918, it was still acceptable to buy, sell, or rob items from ancient tombs, and it seems some people took advantage of this.

In a series of postcards to a friend in 1915, famous New Zealand airman Sir Keith Park (then serving as a young gunner with the New Zealand Artillery) says his fellow servicemen would go out at night and collect jewels and other items from within nearby tombs. He also writes a fascinating description of visiting a pyramid, led inside by a guide who used lit magnesium wire to light the way, which was arguably not the most safety conscious decision.

Nowadays, you can still visit these places and enjoy them as intended, just in ways where the potential damage and degradation is mitigated — much like what we do here at the Museum today.