Matariki, the Māori New Year, is a time to celebrate and come together with whānau, friends and communities, maumahara (remember) the people who came before us and share knowledge, traditions, and skills through wānanga (learning), while looking forward to the year ahead.

Last year for Matariki, we created an activity for tamariki (and the young-at heart!) to make a box kite – you can find the kite-making instructions sheet here (PDF) or on the AFM Kids page. This blog explores kite flying during Matariki and the kites our Air Force used to survive when downed at sea.

Māori kites and Matariki

Kite flying traditions are found around the world, but in Aotearoa New Zealand, kites were flown to celebrate the start of the Māori New Year, when the stars of Matariki (the Pleiades) appears in the midwinter sky.

Māori kites are known as manu tukutuku, manu aute, or pākau (bird wing). In Te Reo, “manu” means both kite and bird, “tukutuku” describes the action of letting go, or to send, and aute is cloth made from bark of the paper mulberry tree, used in kite-making.

Connecting heaven and earth, Māori kites were used for divination, for communicating messages to people far away (including those who had passed on), as well as for child’s play.

According to Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, there were around 17 known types of Māori kite, but only three types have survived. In all, seven original kites still exist, held in museum collections in London, Hawaii, Auckland, and Wellington – you can learn more about those at Te Papa in this video;

Survival at sea

There are many reasons for flying kites, but why would the RNZAF use them? During World War Two, kites were used by air force pilots in life rafts after being shot down by an enemy or crashed at sea.

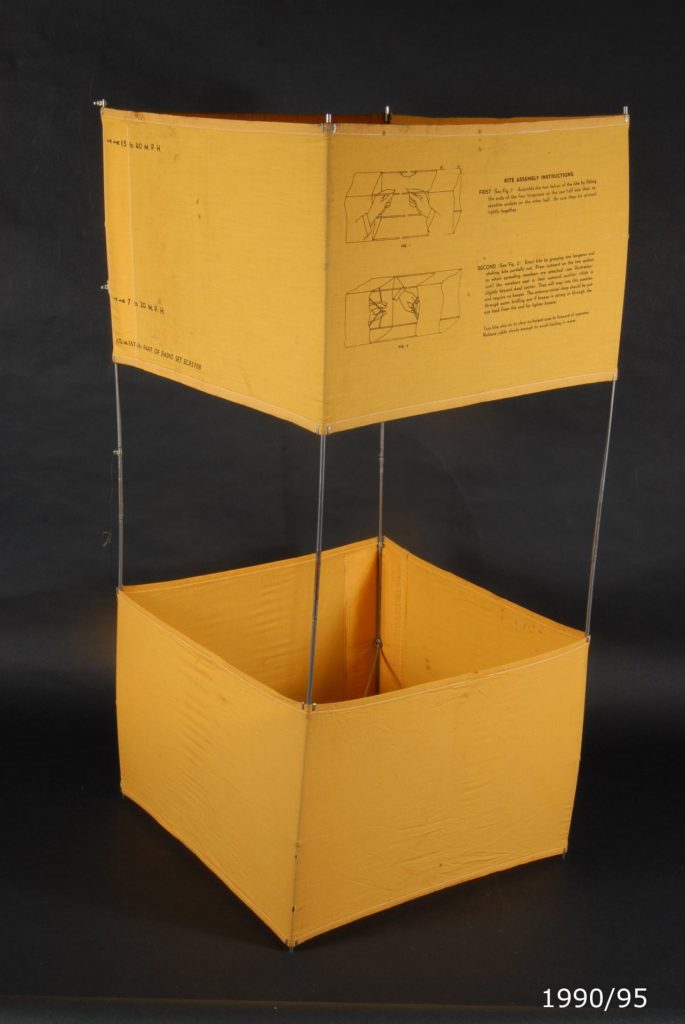

A box kite was used to lift 260 feet (80m) of stainless-steel wire antenna as a flying line. This antenna was connected to a radio called a Gibson Girl, so-called for its hourglass shape which reminded users of the Edwardian “ideal” of the feminine form.

The pilot, who needed rescuing, would launch the box kite, and then try and call for help on the radio. The radio could automatically transmit an SOS (save our souls) signal in Morse Code, which could then enable a rescue attempt.

The above image shows a diagram of an airman in a life raft assembling all the different parts of the box kite. Gibson Girl radios, together with its box kite antenna, saved the lives of many airmen during the war, and the kites were still used until the mid-1980s.

At the time of publication, both the Box Kite and “Gibson Girl” Radio Transmitter are on display in our “Horizon to Horizon” History Gallery – find them at your next visit!